Rich Knudson wants to know why his 802.11ac-bearing iMac from late 2015 isn’t giving him the performance he expects when connected to a new Time Capsule, which also has 802.11ac Wi-Fi networking. He compared AirPort Utility numbers to OS X’s hidden display, and writes:

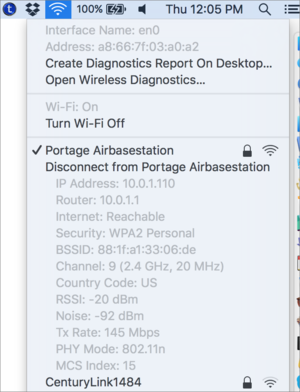

The data rate/Tx [transmit] Rate and RSSI [received signal strength] are very different between Airport Utility and the extended Wi-Fi data you get when you option click the Wi-Fi icon in the top right menu bar.

One of the benefits I was expecting with my new setup was to connect my iMac to the network using wireless-ac and see a step function improvement in data rate/Tx Rate speeds.

As someone who has tested and used Wi-Fi for 15 years, I was curious about this, too. It’s true that a Wi-Fi adapter and a Wi-Fi base station have asymmetrical parameters. The Wi-Fi adapter in a mobile or desktop device almost always has a less-powerful radio and antenna arrangement for reasons of size and battery. (Desktop Macs can use more power, but they’re relying on similar designs.) A base station can produce a much stronger signal and its antenna arrangement has a design optimized for reach and performance; it doesn’t have to play nice with computer or handheld functions, like an adapter does.

So it’s very likely you’ll see an adapter report stronger signal strength from the base station than the base station will report for the adapter. A base station can push out more power in a focused direction, allowing a distant receiver to pick up a signal, and it can also have more receive sensitivity, allowing a faint transmission by the adapter to be heard clearly.

But other reported values should be the same: If you’re looking around the same moment, the data rate should be identical, as that’s a function of the negotiated connection between adapter and base station. Wi-Fi in all its flavors allows devices to move to faster and slower rates as performance improves or degrades. This allows you to move closer to or farther from a base station and maintain a connection. 802.11n and 802.11ac can also use variable amounts of frequency—different channel “widths”—based on the active electromagnetic environment in the ranges they’re employing. Over very very short intervals, from one frame to the next (the wireless data equivalent of a packet), raw throughput could vary by a factor of four.

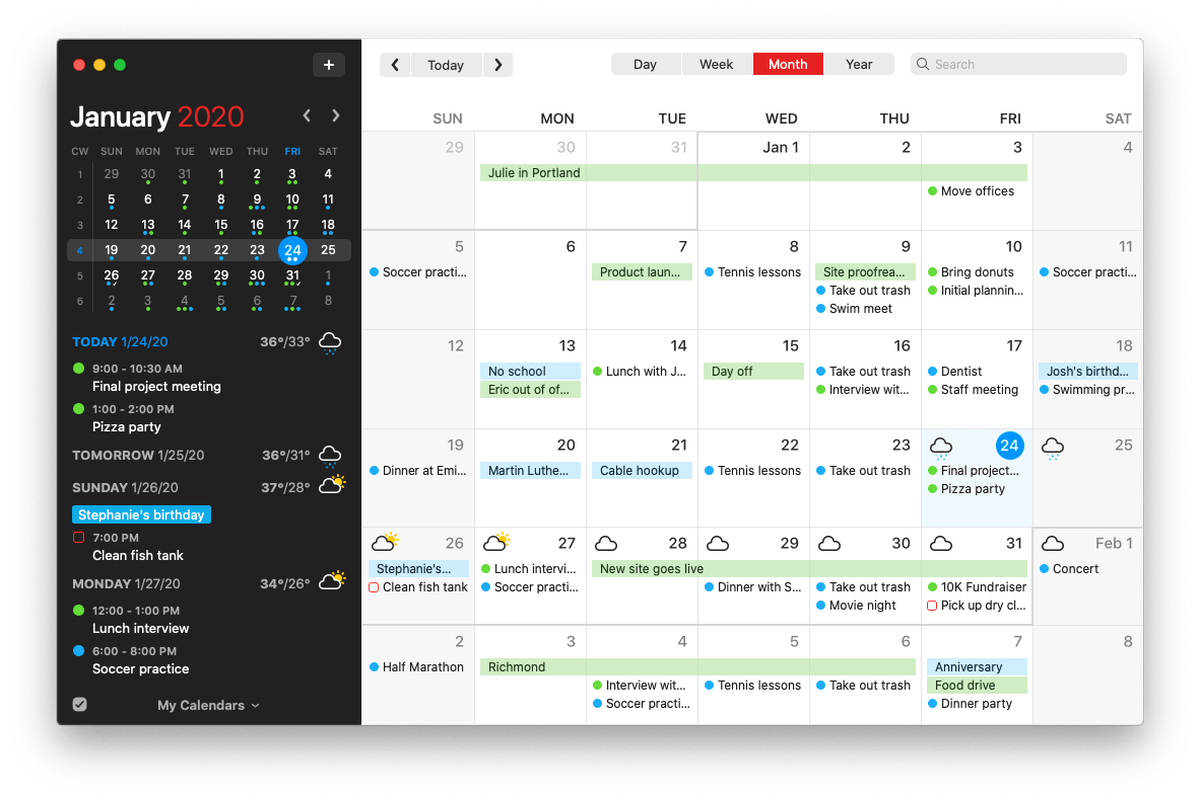

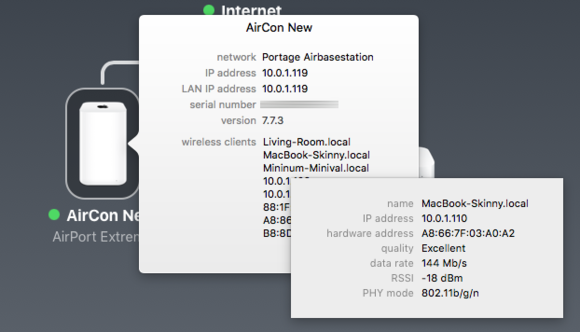

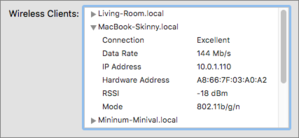

If you want to check your own values, it’s very straightforward. In OS X, hold down the Option key and click the Wi-Fi icon (as Rich notes) and you’ll see detailed diagnostic and performance information. In AirPort Utility 6, click a base station and hover over any entry in the Wireless Clients list to reveal connection details. (You can also hold down the Option key and click Edit, and in the now-revealed Summary tab, you can click the expand triangle in the Wireless Clients list to sell details as well.)

I asked Apple about this situation, as it seemed like there were disparities. The firm replied that because Wi-Fi environment changes constantly, the values represent essentially a snapshot of a sliver of time—if the snapshot in OS X and AirPort Utility aren’t the identical moment (probably down to milliseconds), the details will vary slightly. AirPort Utility only refreshes after launch if you press Command-R, then new values are loaded.

Rich sent screen captures showing that the base station thought it was connected at a rate of 351 Mbps, while his Mac said 117 Mbps. That’s obviously a threefold difference, but because of constant rate changes, it’s within expected ranges.

To get a better sense of network hotspots and performance, you can use tools like WiFi Explorer and NetSpot. And if you’d like to check actual throughput, instead of reported network speeds, jperfis your best bet. It requires the installation of Java, but not in a Web browser, so you’re not exposing your self to Web-based or remote attacks. You install jperf on a target Mac connected via ethernet to the base station, and then on a Mac connected by Wi-Fi. You can then set one as a server and one as a client to run tests.

[Source:- Mac World ]