ARM Holdings has been often described as the UK’s leading technology company. And while it might not be a household name, many products that qualify rely on the Cambridge company’s brainpower.

Samsung’s Galaxy smartphones, Apple’s iPad tablets, Amazon’s Kindle e-readers, Nest’s smart thermostats, Ford’s cars, DJI’s drones, Canon’s EOS cameras and Fitbit’s fitness trackers barely scratch the surface.

So, news that the business has accepted a £24.3bn offer from Japan’s Softbank has wide-ranging ramifications.

Impressive. ARM must be making lots of chips then?

Image copyrightARM

Image copyrightARMNo.

ARM doesn’t actually manufacture computer processors itself, but rather licenses its semiconductor technologies to others.

In some cases, manufacturers only license ARM’s architecture, or “instruction sets”, which determine how processors handle commands. This option gives chip-makers greater freedom to customise their own designs.

In other cases, manufacturers license ARM’s processor core designs – which describes how the chips’ transistors should be arranged. These blueprints still need to be combined with other elements – such as memory and radios – to create what’s referred to as a system-on-chip.

As a result, when you hear talk of a device being powered by a Samsung Exynos, Qualcomm Snapdragon or Apple A8 chip, it is still ARM’s technology that is involved.

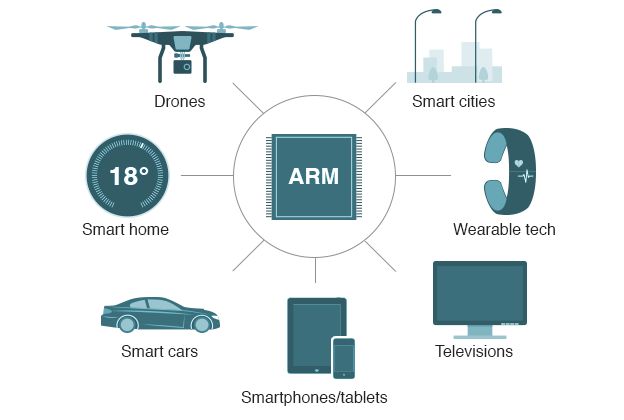

ARM microchips used in many technologies

- Televisions – Many modern televisions now run apps, allowing them to provide Netflix and other internet-based services, which are powered by ARM-based processors. The company’s technology is also used in TV set-top boxes and remote controls

- Smartphones and tablets – ARM’s chip designs are at the heart of the vast majority of smartphones as well as many tablets. E-readers and digital cameras typically rely on ARM’s technology as well

- Drones – Drones are just one of a growing number of products to rely on tiny computers called microcontrollers – other examples include the controls for buildings’ air-conditioning and lift systems. ARM estimates a quarter of such embedded computer chips made last year used its technology

- Smart home – Internet-connected thermostats, electricity meters and smoke alarms are among a growing range of products that promise to make our homes safer and more energy efficient. Many use ARM-based chips to help homeowners cut their bills

- Smart cities – Several cities are exploring the use of sensors to cut costs and help their inhabitants. Examples include street lamps that dim themselves when there is nobody close by and parking meters that detect when spaces are empty – or alert nearby wardens when vehicles have overstayed their time slots. ARM believes this sector holds great potential for its business

- Smart cars – ARM-based chips are already used within many vehicles’ infotainment systems to let them show maps, offer voice recognition and play music. They also carry out the calculations needed to run driver assistance systems – working out when to trigger automatic electronic braking, for example – and are being used within prototype self-driving systems

- Wearable tech – From fitness trackers to smartwatches, much of the most popular wearable tech has relied on ARM-based chips for several years. Now, virtual reality and augmented reality headsets are the latest kit to feature the company’s technology

Who are its main rivals?

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIntel is often described as its chief competitor because it makes processors based on a different architecture, known as x86.

ARM’s reputation for power-efficiency has helped prevent Intel from making much headway with smartphones, but most Windows devices rely on the US company’s chips.

Another UK-based chip designer, Imagination, attempted to popularise another chip design called Mips, but has had limited success.

So, was ARM a success from the start?

Image copyrightAPPLE

Image copyrightAPPLEHardly.

The company’s origins can be traced back to the success of the BBC Microcomputer in the 1980s.

When its developer, Acorn Computers, sought to make a follow-up, it initially considered using chips made by others.

But eventually, the company decided to make its own processors, whose name ARM stood for Acorn RISC (reduced instruction set computing) Machines.

The resulting computers – the Acorn Archimedes series – struggled to sell. So, Acorn came up with a different business plan.

It created a joint venture with Apple, called ARM Holdings, to make a chip for the American company’s first handheld computer, the Newton, which launched in 1993.

It also flopped. But there was, eventually, a silver lining.

When Apple sold its 43% stake in ARM, it used part of the proceeds to buy Next, which led to the return of its co-founder Steve Jobs.

Although Mr Jobs shut down the Newton division, he would later use ARM-based chips as the basis for first the iPod, then the iPhone and next the iPad.

ARM benefited from the i-products’ huge success. But its focus on low-power usage also meant it had success elsewhere.

Nokia built phones using ARM-based chips made by Texas Instruments. And other licensees included Sony, HP, IBM, Philips and Qualcomm.

Well, £24bn still sounds a lot for a mobile computing chip designer

Image copyrightFORD

Image copyrightFORDARM has also been making in-roads elsewhere.

It reckons its designs now account for about a quarter of all microcontrollers – a term used to refer to small computer chips typically dedicated to one specific task.

These feature in a wide variety of products including:

- electronic passports

- car control systems

- hard disks and flash memory

- lift control systems

- smart cards used to access public transport or make payments

ARM’s technology is also increasingly being used in data centres and networking equipment – such as mobile base stations and routers – so, it should benefit from the imminent shift to 5G.

In addition, the company has itself recently taken over several “internet-of-things” related businesses.

Although the sector is still relatively small, there are forecasts there will be a boom in demand for sensor-laden, internet-connected components that will be built into our homes, streets, clothes – and ultimately, even our bodies.

All in all, ARM says about 15 billion chips based on its designs were shipped last year, representing about a third of all chips used in smart electronic devices.

And it thinks that number represents a fraction of its potential market in a few years time.

Why didn’t anyone else buy it before then?

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESThe danger has always been that if one of the technology giants bought ARM, then it might discourage others from using its designs or, possibly, provoke a larger counter-offer.

So, Apple, Samsung and Huawei – for example – are all happy to use ARM’s designs, but would probably not have wanted each other to have owned it outright.

Intel had long been rumoured to have been a potential bidder, but such a merger would be difficult to clear with competition watchdogs.

As one of Japan’s biggest mobile networks, Softbank’s business has little overlap with most of ARM’s customers – which may mean they won’t see the takeover as a threat.

Even so, there would be concern if there were any hint that ARM’s fees might be set to rise as a result.

Softbank is paying a 43% premium over ARM’s closing share price last week and is financing the deal by taking on more debt.

Presumably, the Tokyo-based company believes our appetite for smart products to be very large indeed.

[Source:- BBC]