ARM on Monday announced a new chip design targeting high-performance computing — an update to its ARMv8-A architecture, known as the Scalable Vector Extension (SVE).

The new design significantly extends the vector processing capabilities associated with AArch64 (64-bit) execution, allowing CPU designers to choose the most appropriate vector length for their application and market, from 128 to 2048 bits. SVE will also allow advanced vectorizing compilers to extract more fine-grain parallelism from existing code.

“Immense amounts of data are being collected today in areas such as meteorology, geology, astronomy, quantum physics, fluid dynamics, and pharmaceutical research,” wrote ARM fellow Nigel Stephens. HPC systems over the next five to 10 years will shoot for exascale computing, he continued. “In addition, advances in data analytics and areas such as computer vision and machine learning are already increasing the demands for increased parallelization of program execution today and into the future.”

The development shows that ARM doesn’t want to be left behind in the race toward exascale computing, which would theoretically be a thousand times more powerful than a petabyte scale computer and capable of performing one exaflop of calculations per second.AMD, IBM, and Intel are all striving for it, while governments also jostle for dominance in high-performance computing.

Fujitsu will be the first to install the new chip design, PC World reported, in its Post-K supercomputer.

The announcement comes just about a month after Japan-based SoftBank announced it would purchase ARM for a whopping $31.4 billion, making a long-term bet on the Internet of Things market.

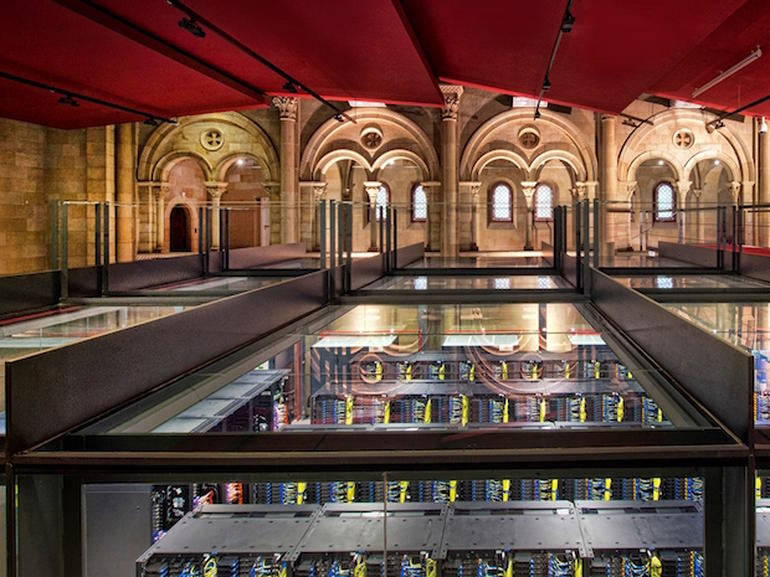

A chapel in the heart of Barcelona Univesity is home to one of Europe’s most powerful supercomputers – and a mobile chip-based successor is under development.

A chapel in the heart of Barcelona Univesity is home to one of Europe’s most powerful supercomputers – and a mobile chip-based successor is under development.The BSC, managed jointly by the Spanish government’s ministry of education and science, the Catalan government’s department of education and universities, and the Polytechnic University of Catalonia, is a research center but also serves as infrastructure for other researchers in both Spain and across Europe.

Its crown jewels, kept in a 120 square metre chapel, is the MareNostrum, a supercomputer made by IBM which runs on Linux, and has fibre connections to universities and European research centers. When it was released in 2004, it became the fourth most powerful computer in the world and first in Europe.

What’s more challenging is having processors that crash, Valero said – which is why BSC researchers are working on techniques that allow calculations to switch to another processor when one fails. That way, the research is able continue as if nothing had happened. Fortunately, this kind of situation is rare.

“The third pillar of science”

The supercomputer serves a good list of projects. Seventy percent of its capacity is destined for European researchers and 24 percent for Spanish projects. The remaining six percent is reserved for a diverse array of BSC initiatives.

Valero likes to say that “supercomputing is the third pillar of science,” after theory and laboratory research. With MareNostrom performing 1015 operations per second and storing massive amounts of data, it enables countless applications. “It’s like a microscope that can be used in any field,” said Valero, who began teaching at the UPC in 1974 and still speaks passionately about supercomputing.

For example, the BSC director says Repsol, a global energy company based in Madrid, uses MareNostrum to develop new algorithms to track the seabed and predict with increasing accuracy where there may be oil, bringing considerable savings to an industry where a 25 percent chance of success is considered high.

Iberdrola, another Spanish energy company concentrating on wind power, found that MareNostrum enabled it to study the best location for building turbines in wind farms. With the simulations carried out in the supercomputer, performance has been raised by five percent. BSC researchers are now working on a second phase of the project to get accurate forecasts of energy production in the short term, which are useful for renewable energy companies to plan feeding back energy to the grid.

In the same area of engineering, the center is working on building biosimulators, which show in detail how the heart and respiratory system work.

In the area of life sciences, the center has become an essential partner for different institutions in Barcelona and Spain which are working on issues of genomics and drug development. A few months ago, an article published in Nature highlighted the Smufin software developed by the BSC, looking at how it facilitates the comparison of genomes, both for clinical use and research.

Moreover, the BSC hosts the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which stores genome and phenome data on over 100,000 people, from 200 centres and research groups all around the world. It is a fundamental resource for the advancement of personalised medicine. The amount of data generated is amazing and the concern for security inevitable. But the BSC’s director said that “bioinformatics data is easier to protect than data from thousands of applications we use every day on mobile phones”.

Dreams for the future

While exaflop (1018) machines are predicted to hit the market by 2018, Valero isn’t holding his breath. “We need 100 million processors and these processors have two problems. The first is the cost of energy, which would be in any case substantial: around €500m per year. The second is that as the number of processor grows, ‘component failure rate’ becomes a serious issue,” he said. “We should point to 2022,” he said, but admitted that he’s “not a guru” on this issue.

He nonetheless predicts the future lies in cognitive computing and is convinced that mobile technology can increase the power of supercomputers without increasing energy expenditure. After all, the most powerful supercomputer in the world, Tianhe-2, runs up a bill of 25 megawatts per year, or roughly €25m.

Mobile power

As a result, the BSC is already working on the development of Mont-Blanc, a supercomputer based on ARM chips more commonly associated with smartphones; there’s already a prototype in the same chapel where MareNostrum is housed. Mont-Blanc is “what’s next”, said Valero. It’s a great challenge with a budget of €11.3m (€8m from the EU) for its second version, set to be completed next year. For the moment, the prototype is testing different applications.

“Now it’s possible to make competitive supercomputers in Europe, because technology is available and the environment is favorable. Our dream would be to create the ‘Airbus’ of supercomputing,” Valero said.

But in the short term, the next logical step is updating MareNostrum – one of the requirements of the European Union’s PRACE (Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe) program, which mandates that a supercomputer in either Germany, Italy, France or Spain has to be renewed each year to maintain European competitiveness in supercomputing. Yet patch-type solutions like adding more processors are not enough. Valero made it clear that the whole supercomputer must be overhauled.

This will be the fourth version of MareNostrum. The third cost €22.7m including taxes and associated overheads such as power and cooling. Its successor is expected to cost more or less the same when it’s finished next year. With the new update, the BSC could be among the best in the Linpack Benchmarck again, even if “it’s not the only priority” for the center, according to Valero.

The BSC aims to combine a good position in the Top 500 list, with an architecture that enables it to serve as many users as possible. Then, old components would be recycled in other supercomputing centers in Spain. “As good Catalans, we don’t throw anything away,” said the BSC director.

Now it ranks 57th on the Linpack Benchmarck. The number one position on the list is taken by the Chinese Tianhe-2 machine which delivers 33.86 petaflops (quadrillions of calculations per second).

Thanks to an upgrade completed a few years ago, MareNostrum now has a peak performance of 1.1 petaflops, with Intel 48,896 Sandy Bridge processors in 3,056 nodes, and 84 Xeon Phi 5110P in 42 nodes. The system notches up more than 104.6TB of main memory and 2PB of GPFS disk storage.

The supercomputer almost never stops. It churns through €1.4m a year in electricity, a bill that the center didn’t want to increase with a uninterrupted power supply (UPS).

If there’s a power outage, the machine can still run for two or three hours, but not longer. The supercomputer has a system that makes regular checkpoints to restrict information lost in case of power failure. While that may seem problematic for projects that use large amounts of data, energy savings carry greater weight.

[Source:-ZD net]