As Hyperloop One imagines it, the transportation of the future involves a blend of Uber, the monorail, and supersonic speed. Yesterday, the company and the Danish architecture firm BIG revealed renderings that show how the transportation system will look—assuming the technology is ever fully developed, of course.

Hyperloop One is just one of several startups vying to commercialize Space X’s Hyperloop design proposal (Space X itself is not involved with any further developments). The concept involves high-speed travel courtesy of pods that levitate in a tube and are propelled by electromagnets. Hyperloop One is currently testing technology that could make Musk’s vision a reality, and hopes to have a functional prototype by 2020. The first functioning system has been rumored to be destined for California and Russia. But now, Hyperloop has announced it’s working with the United Arab Emirates to build its first commercialized system, connecting Dubai to Abu Dhabi. (The wide-open desert expanses are likely easier to design for than California’s earthquake-prone terrain.)

Bjarke Ingels Group has been working with Hyperloop One since May to develop the design itself, and this week released a video of its ideas.

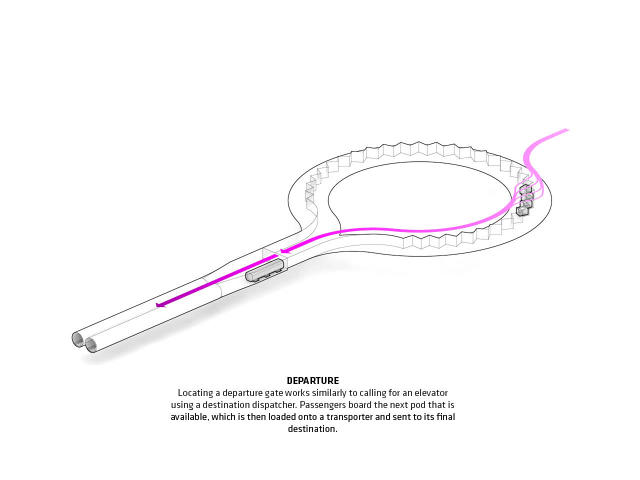

Picture this. You’re a desk jockey in Abu Dhabi. You pull up an app to figure out the most efficient way to travel the 75 miles to Dubai in order to make it to your mother’s birthday party by the time she arrives in 30 minutes. (This is the scenario in Hyperloop One’s promo video, so bear with us.) Being a member of the futuristic sharing economy, you don’t have a car so the options are bus (three hours), walking (47 hours, if you even survive the desert heat), boat (four hours), or plane (48 minutes). Then there’s the Hyperloop, which comes in at a paltry 12 minutes. You select this option and the app directs you to a gate in a nearby terminal.

You arrive at the terminal and step inside a pod—each of which has its own “class” just like an airplane or train—then the pod, which is autonomous and set on wheels, is directed by a control center to an area where it links with four other pods before rolling into a transporter. The transporter then travels to the Hyperloop tube and is shot at speeds of up to 700 miles per hour, courtesy of a still-nebulous electronic propulsion and magnetic levitation system, to a terminal in the shadows of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa. There, the pods exit the transporter to the street level, and travel autonomously by road to your final destination. The heart of the experience revolves around eliminating as much passenger waiting time as possible and arriving at your final destination with as few interruptions as possible. Behold the remarkable future of mobility.

Earlier this year, Hyperloop One announced that BIG, engineering firm Arup, and architecture firm Aecom would be its design partners for the project. In a news release, Ingels said:

“With Hyperloop One we have given form to a mobility ecosystem of pods and portals, where the waiting hall has vanished along with waiting itself. Hyperloop One combines collective commuting with individual freedom at near supersonic speed. We are heading for a future where our mental map of the city is completely reconfigured, as our habitual understanding of distance and proximity—time and space—is warped by this virgin form of travel.”

The challenge for BIG and its partners is to give form to a technology that doesn’t really exist. Startups and researchers alike are still prototyping the idea. Hyperloop One held its first public test earlier this year—essentially a two-second-long trip of a sled shooting down a short track. Despite its success, it was nowhere near being able to transport people. Ingels invites this type of challenge. “This is the first time we’ve really been able to . . . give a form to something completely new,” he told Rolling Stone. Here, Hyperloop One is tapping into BIG’s reputation as expert communicators of futuristic design, and Ingels’s natural showmanship.

The mirrored pods are sleek and look irresistibly comfortable and humane inside—nothing like the cramped accommodations in airplanes or on Amtrak. The elegant terminals could be a scene cut from Gattaca. If swanky PanAm and Concorde lounges of the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s embodied the golden age of travel, this surely represents the forthcoming platinum era. The caveat being ifit ever comes.

Today, designers are tasked with humanizing all sorts of emerging technologies, and showing consumers how those technologies might be integrated into their daily lives. Take artificial intelligence. In the mind of Stanley Kubrick, it becomes a villain. But to designer Yves Behar, it’s as benign and domesticated as a piece of furniture, illustrated by his robotic bassinet. In this sense, architects have a valuable role to play in how the infrastructure of new mobility systems is integrated into cities and our daily lives.

Yet creating an image of a technology before that technology is proven is a challenge. In architecture tropes, BIG is developing a form before the function is even determined. There’s no guarantee that the Hyperloop’s technical capabilities will support the type of experience BIG has envisioned. After all, self-driving cars alone are perpetually five years on the horizon. So while the ambitious design offers plenty to salivate over, it might be another bill of goods on the future of travel. But hey, we can always dream.

[Source:-Co design Blog]