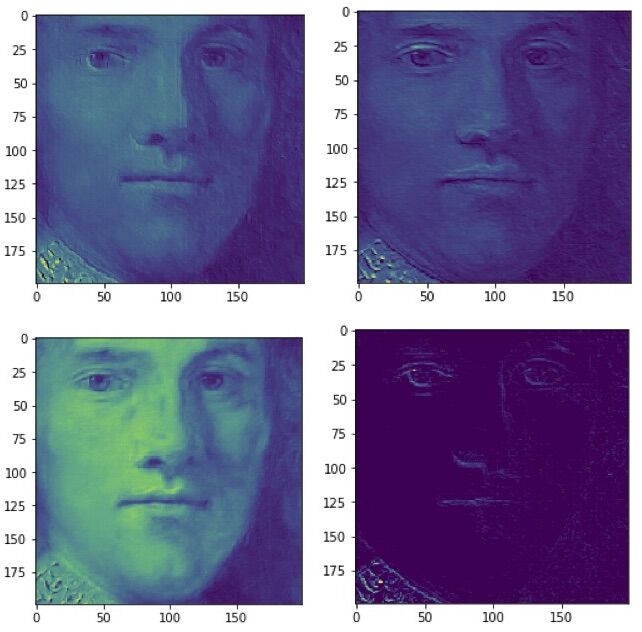

“Activation layers” of A-Eye’s neural network when it analyzed the 400×400-pixel face fragment at the top of Rembrandt’sPortrait of a Young Gentleman. Image courtesy of Steven and Andrea Frank.

, came in at 41 percent; both The Polish Rider (ca. 1655) from the Frick Collection and The Man with the Golden Helmet (ca. 1650) from Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie were deemed 74-percent Rembrandt; and one of the most recently disputed discoveries, Portrait of a Young Gentleman (ca. 1634), owned by the Dutch art dealer Jan Six, came in at 55 percent, barely over A-Eye’s threshold for a genuine Rembrandt.

Ferdinand Bol (attributed to), Portrait of an Old Lady, Possibly Elisabeth Bas, c. 1640–45. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

,

, and

and specially made copies.)

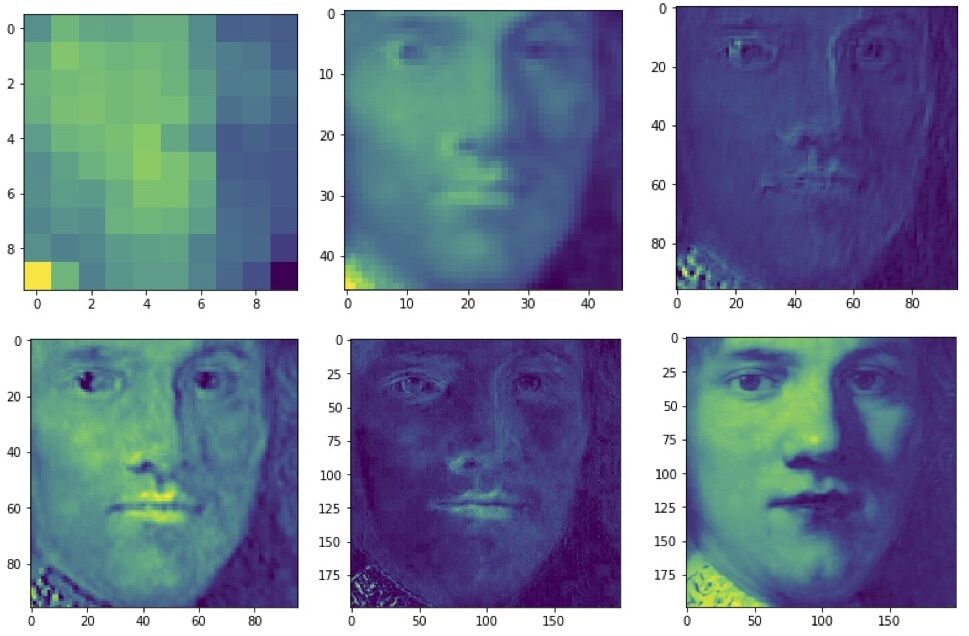

A-Eye picks out the most pictorially interesting/meaningful fragments from an original. Image courtesy of Steven and Andrea Frank.

. But authenticators need not worry about their jobs just yet. Like infrared reflectography and other forms of non-invasive imaging, AI is just another tool to add to their kit.