With one dramatic no, a major artist has just escalated the culture world’s war against Donald J. Trump.

For more than 20 years, the artist Christo has worked tirelessly and spent $15 million of his own money to create a vast public artwork in Colorado that would draw thousands of tourists and rival the ambition of “The Gates,” the saffron transformation of Central Park that made him and Jeanne-Claude, his collaborator and wife, two of the most talked-about artists of their generation.

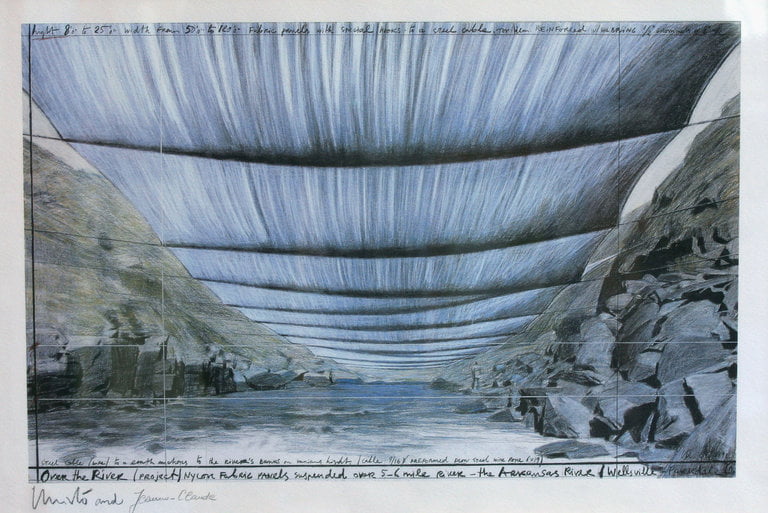

But Christo said this week that he had decided to walk away from the Colorado project — a silvery canopy suspended temporarily over 42 miles of the Arkansas River — because the terrain, federally owned, has a new landlord he refuses to have anything to do with: President Trump.

His decision is by far the most visible — and costly — protest of the new administration from within the art world, whose dependence on ultra-wealthy and sometimes politically conservative collectors has tended to inhibit galleries, museums and artists from the kind of full-throated public disavowal of Mr. Trump expressed by some other segments of the creative world. Last week, the artist Richard Prince fired an opening salvo, returning a $36,000 payment for an artwork depicting Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter, owned by her family.

The Christo project, titled “Over the River,” conceived with his wife, who died in 2009, has been fiercely opposed in state and federal court by a group of Coloradans who contend that it will endanger wildlife and cause other problems in Bighorn Sheep Canyon. Almost six miles of fabric panels were to be erected over the river for two weeks, at a cost that could have exceeded $50 million. Christo, who sells artwork depicting his proposed projects to pay for them completely on his own, has prevailed in every court battle and is awaiting a decision by a federal appeals court that would represent a final stand by opponents.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

But in an interview on Tuesday, he said that even if he won the case, he would no longer go forward with the work.

“I came from a Communist country,” said Christo, 81, who was born Christo Vladimirov Javacheff in Bulgaria and moved to New York with Jeanne-Claude in 1964, becoming an American citizen in 1973. “I use my own money and my own work and my own plans because I like to be totally free. And here now, the federal government is our landlord. They own the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord.”

Asked to elaborate on his views of the new president, he said only, “The decision speaks for itself.” He added, “My decision process was that, like many others, I never believed that Trump would be elected.”

The establishment art world is slowly beginning to become more vocal about Mr. Trump, invoking the power of past protest movements, like the Art Workers Coalition, whose Moratorium of Art to End the War in Vietnam pressured museums to close for a day in October 1969, and led the next year to an Art Strike Against Racism, War and Oppression, which drew picketers to the Metropolitan Museum of Art because it declined to shut its doors.

In late November, more than 150 prominent artists, curators and gallery workers picketed in front of the Puck Building in Downtown Manhattan, owned by the family of Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump’s husband and now a senior adviser to President Trump. Under the banner of a continuing social-media and protest movement called Dear Ivanka, critics of the President have directed almost daily condemnations of his actions and policies to his daughter, a prominent art collector. And on Inauguration Day, dozens of galleries — and a few public art institutions — closed in cities across the country as a part of a movement, J20, that plans to broaden protest activities in the coming months to address issues like racism, immigration and gentrification.

Aesthetic refusal as a form of protest does not have universal support in the art world. Some see it as ineffective, a defeatist position that denies the power of expression itself to effect change.

“I would argue that this project, on a river that traverses both red and blue states, could draw attention to the importance of federal land management and stewardship of the environment,” said Tom Eccles, the executive director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College and former director of the Public Art Fund in New York. “If anything, Christo’s projects promote a sense of collective wonder, something we need more than ever right now.”

Hope Hicks, a spokeswoman for the White House, said it had no comment.

Christo, whose work usually involves monumental wrapping or draping, a kind of beautifying abstraction of architecture or landscape, is known not only for “The Gates,” but also for highly visible projects like “Wrapped Reichstag,” in Berlin, realized in 1995 after more than 20 years of planning and proposals. Last year, “The Floating Piers,” a yellow-orange walkway of fabric atop 220,000 interlocking polyethylene cubes on Lake Iseo in the Lombardy region of Italy, drew 1.2 million visitors.

The Colorado project would have been the largest work Christo had ever attempted in America. In interviews, he spoke about how the idea came about in 1985, during a project in which he and Jeanne-Claude had wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris. “We looked up at the fabric, and it was so beautiful, silvery and shimmering in the reflected light of the river, and we smiled at each other,” he said.

The two inspected dozens of rivers and selected a length of the Arkansas, partly because it was a popular rafting spot, and the canopied fabric, stretched over steel wire cables anchored on the banks, would be best seen from beneath, on the water itself. The project, expected to take more than two years to construct, was to remain in place for two weeks, during an August, before, like all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s projects, being dismantled.

In court, Christo argued that he had taken every step possible to prevent long-term damage to the river, land around it, or animal or plant life. The group that has opposed him, Rags Over the Arkansas River, or ROAR, has argued that the federal Bureau of Land Management, in approving the project, failed to take sufficiently into account its possible threat to bighorn sheep and the impact on traffic on U.S. Highway 50 through the canyon. On Wednesday, Joan Anzelmo, a spokeswoman for ROAR, said it was “ecstatic” to hear of the decision, no matter what the artist’s reasons. “This means local people will now be protected,” she said, “as well as wildlife, birds and fish.”

In the interview on Tuesday, Christo said the Job-like patience required in seeking approval for his projects has always been an element of the spirit of the projects themselves. He needs to feel passion about them, in the same way that a more traditional painter or sculptor does, he added. But in this case, “that pleasure is gone” because of the nature of the new administration.

“I am not excited about the project anymore,” he said. “Why should I spend more money on something I don’t want to do?”

[Source:-The New York Times]