Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders had something to say about it. “Google is too big, too powerful, and its anti-worker actions will end when we are in the White House,” he tweeted. “We are going to break up Google and stand up for workers against powerful tech monopolies.”

Ramesh Srinivasan is a Bernie Sanders campaign surrogate and author of Beyond the Valley: How Innovators around the World are Overcoming Inequality and Creating the Technologies of Tomorrow. The book’s anodyne title belies its fierce politics: like Sanders, Srinivasan believes that massive tech companies have grown unaccountably powerful and must be confronted, not courted and appeased as the Democratic Party establishment has done for decades.

Jacobin’s Meagan Day spoke with Srinivasan about the internet’s migration from the public to the private sphere, the political agenda of big tech, and the promise that remains of an internet for people, not for profit.

To what extent was the internet itself actually created by public investment, and to what extent is that creation now privatized?

The date Beyond the Valley was released was October 29, which marked the 50th anniversary of when my colleague Leonard Kleinrock at UCLA attempted to send the word “login” as a message to Stanford across the ARPANET network. The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network was publicly funded by US taxpayer money and was foundational in the establishment of the early network that turned into the larger internet.

There would be no internet without public funding, public subsidies, and public investment, and that’s generally true across the board. Since then, the infrastructures of the internet have been appropriated by private corporations, for private benefit, to support private extractive purposes.

Not only has the public been left uncompensated, but the public is also increasingly manipulated, surveilled, disenfranchised, and exploited by the private corporations that have staged a takeover of the internet.

There was a saying in your book, apparently popular in tech circles, that really jumped out at me: if you’re not the customer, you’re the product. Can you explain what that means?

In Silicon Valley, this is something of a glib, almost self-celebratory phrase.

Traditionally when consumers enter into relationships with businesses, there is a set of mutual agreements and understandings that you will not be manipulated by the services that you pay for. That relationship has been completely turned on its head when it comes to the way tech corporations function. They will do everything possible to take us down behavioral rabbit holes and seduce, addict, track, extract, and manipulate our experiences.

In other words, we are the labor. Yet none of that is compensated, and all of it is productized. And the ways in which it’s productized are subject to mechanisms that serve one purpose, which is corporate profitability.

We proceed without an understanding of how we’re being tracked and being manipulated, how very intimate aspects of our lives are being bought and sold in ways over which we have absolutely no visibility or understanding. No longer do we have the ability to be relatively autonomous or sovereign. It is a toxic model that has deeply sociopathic elements.

Tech companies cling to an image of political neutrality. But they exist to maximize profit for themselves, and to that end, politics is necessary for them to engage in. How fictitious is that mask of political neutrality that they’re presenting to the public?

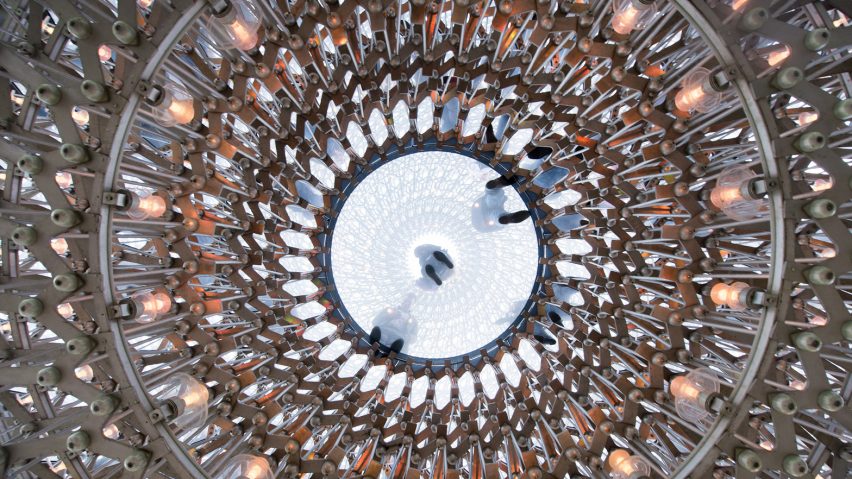

I’ll start by making the point that technology companies like to portray themselves as public-facing, and in that way misrepresent what they are. For example, Apple used to call its retail centers “town squares.” The entire idea is to take over and capture the public discursively through branding, through architecture, through corporate slogans. Tech companies brand themselves as public services when in reality they exploit public labor. So I think in that sense they’re attempting to appear not just apolitical, but almost beyond political, or above politics.

The second point is people have long treated internet technologies in particular — though this is true throughout the history of digital technology and science itself — as morally neutral. We tend to think of technologies as almost teleological attempts to maximize efficiency, just linear instruments of progress. We think of them as agnostic, simply the creation of neutral scientists, neutral engineers.

What I seek to expose in my book is that the political biases, the racial biases, the economic biases, the geographic biases, the gender biases of technologists are fundamental to shaping and impacting the technologies they create, which either open up or foreclose on the life chances for people who are implicated by their systems. So they are profoundly political in that sense.

Now to discuss their political activity itself. Google is one of the biggest lobbyists in the American government. Meanwhile, Amazon already does work with ICE, and a lot of these companies are very cozy with the military. Their goal is to maximize not just their profit, but their overall speculated valuation, and it doesn’t matter who ends up on the chopping block as a result of that.

When Mark Zuckerberg says that Facebook will run all political ads because it’s a matter of free speech, what he’s actually doing is emboldening a world where those who have more power are provided with the ability to abuse that power on Facebook’s platform. Meanwhile, when a company like Facebook or YouTube designs its systems to make visible content that is more extreme, more hateful, more disinformation-based, that’s all done with the intention of locking people in. And that is a political choice, based upon a private self-interest, never mind the consequences for the rest of us.

These companies are intruding upon our political life, claiming the language of democracy and the public interest, when all they are interested in doing is supporting their own bottom lines, their own investors. They do not care about their impact on democracy. It’s quite clear that they do not care.

Disruption is the big word in tech. It’s supposed to be a positive concept, tied to innovation, but obviously sometimes disruption has dire consequences. For example, when full-time jobs get disrupted by gig economy work that pays less and offers no benefits, and breaks industries and breaks workers’ power in those industries. How are corporations using digital technology to erode the gains of workers and maximize profits at those workers’ expense?

Companies like Uber and Airbnb call themselves technology companies, but what they’re actually doing is monetizing and hijacking an economy and making it more unequal. They’re overtaking every industry and every sort of transaction imaginable. They claim to merely facilitate transactions between you and me, but what they’re doing is exploiting those transactions.

The goal is to cut costs. And the two major costs that traditional businesses often have to pay for are labor on the one hand, and supplies and inventory and space on the other hand. Uber doesn’t own hardly any vehicles, and it doesn’t actually employ almost anybody — this is the gig economy fissuring of work. Gig workers for companies like Uber make far less than the minimum wage, are unable to collectively bargain, are not provided benefits, not provided insurance unless they have a passenger in the car, and so on. So they’ve cut costs on vehicles and on labor, but meanwhile, they’re stripping these industries of accountability and traditional social contracts.

In many cases, these arrangements are just an intermediary step on the way to automation. Gig workers will become dispensable once these companies gather enough data from them to become dominant in new industries like automated vehicles. Gig workers are essentially data providers to these companies, and in the long run, will be rendered disposable.

Your book finds glimmers of hope in alternative technological initiatives that do the opposite, intentionally preserving the integrity of the social contract and placing people’s well-being at the center of the project. One example is community mesh networks, which I’d never heard of before. Can you explain what these are?

When we engage with the internet today, not only are we subject to the invisible surveillance and extraction of tech platforms, but we’re also subject to the manipulation of internet and mobile service providers. It blows people’s minds when I tell them that mobile service speeds in the United States are more or less equivalent to what they are in Kenya. They are at least a dozen times slower than in South Korea. That is because corporations are not providing high-quality service to people here, because their entire goal is to maximize value and profit in every way imaginable while cutting costs.

In some places in the world, people have realized that they can have internet and intranet connectivity on their terms by establishing and managing it themselves. This is important because there are resources that can be exchanged across a digital or mobile network; there are opportunities for employment that can occur in relation to creating and sustaining that network; and various forms of skills, training, and literacy that can occur through that network.

One example is Rhizomatica in Mexico, the largest community-owned cell phone network in the world. There are multiple indigenous communities in the Oaxaca region in Southern Mexico that are signed onto this project, and each one manages its own network. Previously, these poor communities did not have cell phone access, because private corporations were not interested in them. So they just said, let’s build it ourselves.

And it’s all collectively run. The way they make decisions over this network is democratic and amazing. They sit, sometimes three hundred of them, in a single room and deliberate until they come up with an agreement. Another aspect of it is that their indigenous languages are rarely written, but that’s what they use to communicate, so it’s an empowering practice to be able to communicate over these networks in those languages.

So that’s a cell phone network example, but there are countless other examples from all over the world, both cell phone and internet, from Detroit to Catalonia, some of which I detail in the book.

Another thing you explore in the book is the case of some engineers in Nairobi who’d managed to expand internet access to three hundred thousand people in Kenya without harvesting and monetizing their data. But this sort of begs the question: given that we just talked about how predatory the internet has become, why is it nonetheless important for three hundred thousand Kenyans to have Wi-Fi?

If I had to venture a guess, I’d say that in a world where the privileged are connected to the internet, connectivity becomes kind of a right. Is connectivity a right, even with all of the dangers that it entails?

It is a right, and yes it’s also a very strange gray zone, because of course the goal of big companies like Facebook and Google is to have everybody connect to the internet. We are met with the likelihood that, at least at this time, the expansion of that right is going to coincide with corporate interests.

To return to Kenya for a moment, I make the point in the book that on a macro-level the architecture of fiber optic connectivity itself is built in the image of power. In the same way that it’s very difficult to catch a nonstop flight between the continents of South America and Africa, the internet is architected for those with power and privilege. That means its infrastructure is primarily concentrated in the Western world, but also increasingly in places like East Asia and China.

However, one of the major fiber optic cables that shoots up the East Coast of Africa has a landing point very near Mombasa, which is the second-largest city in Kenya. So that makes connectivity more possible, and through resourcefulness people in Kenya have been able to take advantage of that connectivity. In turn, connectivity provides them with a way to create all sorts of meaningful possibilities for themselves, their families and communities, and their society at large.

And what we have seen occur in Kenya is the flourishing of technological innovation, from hacking mobile phones, to building 3-D printers out of recycled e-waste parts, to building interesting proposals on democratizing access. This is another point I make in the book: the example of Kenya provides us with a completely alternative reading of the term “innovator” as it relates to technology.

Yes, connectivity is a fundamental right. Yes, it should be governed by everybody. But this book is also a story of the creativity and the power and the bravery and the agency of people to shape all resources, including internet connectivity, in their own image.

These alternative examples are inspiring, but it’s also obvious that we’re not going to be able to generalize the values they exemplify unless we take on the big tech companies directly. You’re a surrogate for the Bernie Sanders campaign for president. Does his campaign hold for you the promise of an actual pushback against the power of big tech?

What draws me to Bernie Sanders’s campaign is that he is the one and only candidate who has stood with the workers and with the 99 percent for decades. There is no other candidate with his level of integrity and directness and clarity. Sanders’s campaign centers workers far more than the other candidates, including Senator Warren, whose proposals tend to be top-down and regulatory rather than fundamentally focused on overturning systems of extractive power. And I think that’s a very key distinction. Senator Sanders is a movement-based candidate.

Now to a couple of specific proposals that I think are very important here in relation to the themes that Beyond the Valley covers. First of all, Senator Sanders has proposed that workers have equity in businesses of all kinds. In fact, he even proposes in certain cases that workers have as much as 50 percent of board seats and overall equity in these companies. He’s taking the zero-sum model by which corporations are currently configured and inverting it. His proposals treat workers as dignified members of a society who contribute value through their labor, and as indispensable parts of a democracy, both a broader democracy and democracy at the workplace.

Senator Sanders stands with workers everywhere. For example, as he moves us toward a Green New Deal, he doesn’t turn his back on those who work in the fossil fuel industry — he’s proposing to find them secure work moving forward. The same goes for workers on the chopping block due to likely automation. Sanders is going to be looking for opportunities to support workers who will otherwise be objectified and ignored and rendered disposable. He is the only candidate who has led rallies for worker justice at Amazon.

Senator Sanders is also looking to figure out ways to support a complete inversion of the funding models and the political economy models for internet connectivity, including internet and mobile service providers. He’s announced a massive investment to support municipal and community-run internet service providers, because he understands the same argument that I make in my book, which is that by decentralizing the governance and accountability around technology of all kinds, you can create greater value for everybody.

I’m assisting his policy team with some of their tech platform and digital inclusion proposals, which you’ll be hearing more about soon. But suffice to say that Senator Sanders is going to take on entrenched and corrupt, big corporate interests. And I believe he is by far the best candidate for president in my lifetime.

[“source=jacobinmag”]