The Trump administration is weighing one of the most significant rulings on how the internet will operate in the future — broadly affecting both the U.S. economy and how Americans get crucial information — but the decision is already a foregone conclusion.

Unlike three years ago, when Washington was abuzz over the Federal Communications Commission enshrining net neutrality into hard-set rules, this time around it’s crickets. And that has net-neutrality supporters worried.

The FCC, led by Ajit Pai, whom President Donald Trump appointed this year, has proposed killing the net-neutrality rules the agency passed under the Obama administration in 2015. Those regulations prohibited internet providers such as Verizon Communications Inc. and Comcast Corp. from favoring certain online content, or charging firms like Netflix or Facebook Inc. to deliver their offerings at faster speeds. The rules, shepherded through by then-Chairman Tom Wheeler, treated the internet more like a public utility needed by everyone, like regular telephone service or power, which are regulated by the government.

When Wheeler, a Democrat whom President Barack Obama appointed in 2013, proposed those rules, progressive consumer advocates were thrilled by the idea — but internet providers were livid. Armies of lawyers and lobbyists representing AT&T Inc., Verizon, Comcast and others poured into FCC’s headquarters, about a half mile from the iconic Washington Monument. They came armed with binders, briefs and PowerPoint presentations to confront and cajole FCC commissioners and staff.

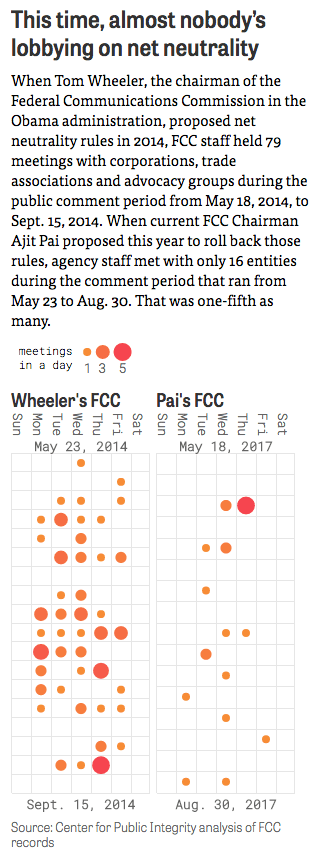

In all, FCC commissioners and staff held 79 meetings between the release of Wheeler’s proposal in May 2014 and the comment deadline in September 2014, more than a meeting every two days, according to an analysis of FCC documents by the Center for Public Integrity. Nearly 63 percent of those get-togethers were with businesses or their trade groups. In the end, the Democratic-majority commission voted 3-2 along party lines to reclassify internet providers as a utility-like “common carrier,” much like telephone service.

But that was then.

Now, three years later, current FCC Chairman Pai, a free-market Republican and staunch critic of government regulations, has proposed to reverse Wheeler’s rules, aggressively pushing a return to classifying internet providers as an “information service,” a designation with far fewer regulations.

The change, which the FCC is likely to vote on later this year, would both neuter the commission’s ability to rein in providers and open the possibility, again, of creating slow and fast lanes for internet traffic — determined in part by who is willing to pay.

This time around, Republicans control the commission. And it’s a lot quieter at the FCC — perhaps because the internet titans see a friend in the chair who isn’t prone to considering other opinions.

From May 18, when the FCC released Pai’s proposed rules, to the end of the public comment period on Aug. 30, commissioners and agency staff met only 16 times with companies and other organizations — about one meeting every six days, or one-fifth as many as when Wheeler issued his proposal in 2014, according to the Center’s analysis.

No one from AT&T set up a meeting. No Verizon. No Comcast. In fact, of the 16 meetings, the FCC met with only two, relatively small, internet providers: Antietam Cable Television Inc., a provider serving a rural county in Maryland, and Home Telephone Company Inc., which provides service north of Charleston, South Carolina.

Most of the people sitting down with the FCC worked for advocacy groups such as the National Hispanic Media Coalition, which lobbies for inclusive and affordable communications, and the Voices for Internet Freedom Coalition, a group of minority organizations that support net neutrality.