When the U.S. begins accepting applications for new H-1B skilled-worker visas today, we can be certain that tech workers from India will make up a large portion of the requests.

Modern tech leaders wear many hats — too many, sometimes. Here are six expert tips from seasoned IT

READ NOW

What we probably won’t know, though, is how many of those applicants are female.

While program data shows which job categories, countries and companies are awarded the most visas, the federal government says it is not tracking applicants’ gender — although the question is asked on the visa application form. The U.S. begins accepting H-1B visa applications on April 1 for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) will not release the gender data. It has rejected a Senate request for the information, as well as public records requests from the IEEE-USA and Computerworld.

“No H-1B visa should ever be issued to an unidentified person — and you can’t know who a person is without knowing their gender,” said Peter Eckstein, the president of the IEEE-USA.

If the USCIS “doesn’t know by now, it’s because they don’t want to know how bad it is,” said Eckstein, regarding the gender of H-1B workers.

The IEEE believes a high percentage are male.

Gender information about H-1B visa holders, critics say, could answer some questions about the program’s impact on the workforce.

The Anita Borg Institute, which advocates for women in technology, believes “it would be very helpful to have better data on the gender diversity of H-1B visa recipients,” Telle Whitney, the president and CEO of the institute, said in an email.

“Our anecdotal experience is that most H-1B visa recipients are men and that this can have a negative impact on increasing the participation of women in the technical workforce,” said Whitney. “It is likely that this also negatively impacts underrepresented minorities.”

Women are underrepresented in technology overall, but particularly worrisome is the talent pipeline. Less than 15% of the bachelor’s degrees awarded in 2014 in computer science and computer engineering went to women, according to the Computing Research Association’s annual survey of enrollments at Ph.D.-granting institutions.

The best source of data for lawmakers on the gender of H-1B workers has been the IEEE-USA. In 2013, Karen Panetta, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Tufts University who was representing the IEEE-USA, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee and told it that as many as 85% of the visa holders are men.

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), who has unsuccessfully sought information about the gender of H-1B workers, cited Panetta’s testimony in seeking an amendment to the 2013 Senate comprehensive immigration reform bill.

Grassley’s amendment prohibited all employers from displacing women 180 days before or after they apply for a foreign worker. The amendment failed, although the comprehensive bill passed the Senate. It was not taken up by the House.

Gender data is a curious omission considering U.S. government initiatives such as TechWomen, which is aimed at supporting “women in leaders in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) from Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East”. And, there’s also the Office of Science and Technology Policy’s stated aimof “increasing the participation of women and girls — as well as other underrepresented groups — in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.”

Computerworld filed a FOIA request for H-1B gender data last year and was told that providing such information would be “unreasonably burdensome.”

“In order to determine the gender of H-1B applicants, USCIS staff would have to manually search each applicant’s immigration file, an unreasonably burdensome and costly requirement because it would require agency personnel to request, ship and manually review thousands of immigration files,” wrote Alan D. Hughes, associate counsel at the Commercial and Administration Law Division of the Department of Homeland Security Citizenship and Immigration Services in denying Computerworld‘s appeal to receive gender data.

In other words: The government chooses to keep track of applicants’ country of origin but not their gender.

There is some data available that can indirectly point to what’s going on.

China and India, in particular, seem more successful at encouraging women to enter technical fields. IEEE research has found that nearly 40% of India’s engineering and technology students are women. But this likely does not represent the proportion of H-1B workers.

The U.S. Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is one federal source of data about gender in the workplace. Its information is not publicly available, but can be used in court cases. The EEOC data for Infosys, an India-based IT service firm, was released last year in an ongoing discrimination case the company is fighting in federal court.

The proportion of women in the Infosys U.S. workforce was 22.5%, according to the court documents. That’s lower than the percent of women in the overall U.S. tech workforce, but not by very much.

The percent of women among Infosys’s Asian workers was still lower, at 19.7%. However, this data doesn’t necessarily show that Infosys H-1Bs skew more male than the overall profession, because IT is a broad category with a number of specialty areas that likely have considerably different gender distributions.

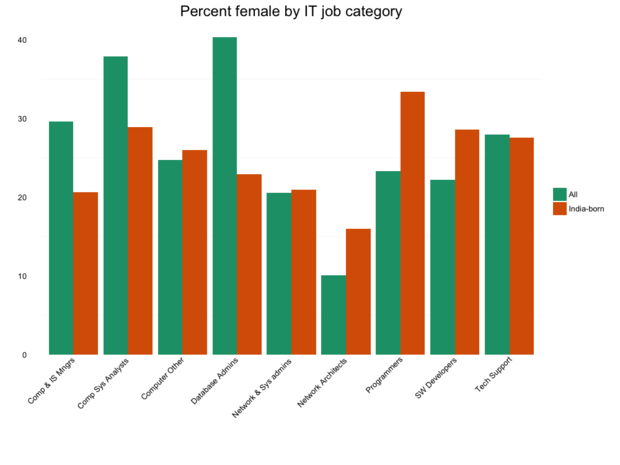

The limited data available about foreign-born IT workers shows a somewhat mixed picture.

A Computerworld analysis of U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data from 2010 to 2014 showed that overall, 27% of the U.S. tech workforce is female. Among people born in India and working in U.S. tech jobs — immigrants and green-card holders as well as those on visas — 27.8% are female, roughly similar. (Want to explore this data yourself? Download the data file as part of our free Insider program.) But more data is needed to complete the picture of H-1B demographics, which may be considerably different than those of foreign-born citizens.

In addition to gender, age is also an issue (although age could be considered a more personally identifiable attribute and thus is not subject to Freedom of Information Act requests). When companies turn to offshore outsourcing and bring in H-1B-using IT contractors, the visa holders tend to be much younger than the employees they are replacing. While that hurts both male and female older workers, the unemployment rates for older women in IT are higher than for men. H-1B workers also increase competition for jobs, and that may be hurting those who already have the most difficulty finding jobs as well.

Advocates say census data and court case records are poor substitutes for the actual data from official visa forms, which remain hidden away in government files.

“If people knew the facts, this would be indefensible,” said Eckstein at the IEEE. “So not releasing the facts is also indefensible.”

[Source:- Computer World]