Ethan Bloch was in junior high school in Baltimore during the dot-com boom.

For his bar mitzvah — the ceremony that welcomes 13-year-old Jewish boys into adulthood — Bloch received $7,000 in cash.

It was 1998 and, like so many amateur traders at the time, he plunged his wealth into the stock market, mostly software and telecommunication names like Lucent and Nortel.

He quickly tripled his money. By age 15, it was all gone.

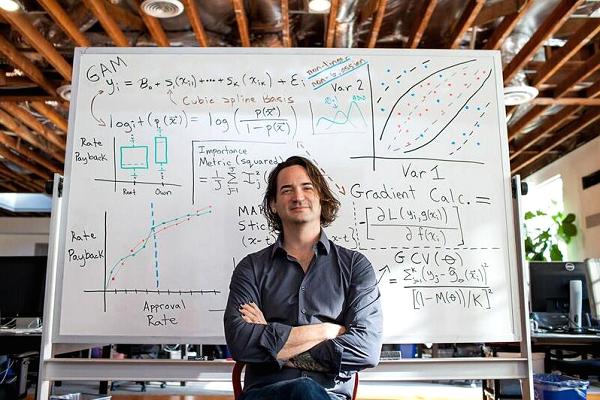

“This knocked me over the head and left a burning curiosity that I still carry today,” said Bloch, now 31, from the San Francisco headquarters of his financial-tech start-up Digit. “I realized I didn’t know s— about how any of this was working.”

Now Bloch is playing into another trend that’s taking over Silicon Valley: Machine learning.

Using the combination of massive data sets, exploding compute capacity in the cloud and a host of analytics tools, entrepreneurs are training computers to make increasingly sophisticated decisions. Eventually, the experts say, we’ll land at true artificial intelligence, where computers are smart enough to train computers.

And it’s going to upend the traditional banking industry.

Helping consumers with their finances

It’s hardly a straight line from the dot-bomb blunder to Bloch’s new gig developing an automated savings tool for millennials. But Bloch says he’s been obsessed with finance for almost two decades, even while running his first software start-up Flowtown, a social media marketing platform.

Bloch sold Flowdown to Demandforce for a few million bucks in 2011. The following year, having banked enough cash to follow his passion, Bloch set out on a mission to improve consumers’ financial health. The tagline on his website is, “Save money, without thinking about it.” The company is initially targeting younger consumers, who’ve grown up in an era dominated by smartphones and a loathing for brick-and-mortar banks.

Digit’s software plugs into a user’s checking account, analyzing expenses and income and determining how much money could be stashed away without the customer feeling it. Based on the personalized algorithm, Digit puts a few bucks or so a week into a savings account, notifying users with a simple text to help them pay off college or credit card debt or prepare for a wedding. It also serves up reminders to eliminate late fees and recently launched a notification bot on Facebook Messenger.

Digit says that it’s saved more than $350 million for its customers.

That includes people like Jenn Chen, a former community manager at a San Francisco software company who’s now in between jobs. Chen has saved close to $16,000 over the past three years using Digit, money that would have otherwise remained in her checking account and more than likely have been spent.

“It started off small and as time went by, I started seeing different ways I could increase that amount and be OK,” she said.

The savings were of particular importance after a hit-and-run accident left her with a hefty out-of-pocket payment for hospital bills.

The changing workforce

According to Goldman Sachs, machine learning and AI will enable $34 billion to $43 billion in annual “cost savings and new revenue opportunities” within the financial sector by 2025, as institutions use technological advancements to maximize trading opportunities, reduce credit risk and lower compliance and regulatory costs.

What that means for the labor force is a complicated equation. The banking sector contracted dramatically during last decade’s financial crisis, with the failure of large institutions like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual and mass layoffs elsewhere. Three of the four largest U.S. banks — Citigroup, Wells Fargo and Bank of America — have fewer employees than they did in 2008.

Jobs most in jeopardy from here are those that lend themselves to automation. Bank tellers will see an 8 percent decline between 2014 and 2024, and the number of insurance underwriters will drop by 11 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. On the flip side, financial firms are hiring software developers and data scientists, areas of employment growth.

Arvind Purushotham, a managing director at Citigroup’s venture investing arm, is backing start-ups in fraud detection and security whose technology can potentially be applied internally at the banking giant. While there’s a shift in the skills required to meet the financial challenges of the future, the problems are still being solved by people.

“We think of human-assisted AI and AI-assisted humans,” said Purushotham, “There are some things that humans can do that software programs can’t hope to catch up to in decades.”

Expanding the lending pool

The problem Douglas Merrill is trying to tackle will require sophisticated machines.

Merill, who spent five years as Google’s chief information officer, is the founder and CEO of ZestFinance, a Los Angeles-based start-up that’s out to end the predatory system of payday lending by building algorithms that can underwrite people with little to no credit history.

(He’s among a handful of ex-Googlers applying computer science to finance. Consumer lender Upstart was created by former Google executives and is led by Dave Girouard, who previously ran Google’s enterprise business. PeerStreet, a marketplace that matches real estate with investors, was co-founded by Brett Crosby, a former product marketing director at Google.)

Merrill, who has a Ph.D in cognitive science from Princeton University, lives and breathes this stuff.

From his vantage point, true machine learning is almost entirely absent from the lending industry despite a rapid acceleration over the past half-decade in online banking and underwriting. Consumer lenders like LendingClub, Prosper and SoFi have built substantial Web-based businesses using technology, but they’re still targeting borrowers with good, if not pristine, credit.

That approach does nothing for Americans who struggle to make ends meet and rely on cash advances from one of the country’s 20,000 payday lenders that populate mostly low-income areas.

ZestFinance is looking for non-traditional data — information that can’t be found in credit files — to determine the types of behavior that can help predict whether someone will repay debt. It turns out that a prospective borrower who fills out an application in all capital letters is a greater-than-average credit risk.

While mounds of data exist that would help in developing new credit models, much of it sits in places that are very difficult to reach. For example, finding out if a bank account is open can be “super challenging,” Merrill said.

“I didn’t foresee how hard would be to get access to a large number of those third-party data streams,” said Merrill, whose 100-person team includes more than 30 data science and machine learning experts. “To run a big data and machine learning shop you have to have big data and machine learning.”

This week, ZestFinance introduced the Zest Automated Machine Learning (ZAML) platform, opening up the technology to any bank, credit card issuer or auto finance company.

Merrill is also testing his algorithms in perhaps the world’s greatest ocean of messy data: China.

Through partnerships with e-retailer JD.com and Internet search provider Baidu, ZestFinance is aiming to help create a system for lending to half a billion people who lack any credit history.

“Lenders in China are beginning to use these advanced techniques that analyze non-traditional variables, whether search, shopping or other data, to form the backbone of a new credit infrastructure,” Merrill wrote recently in Chinese business publication Boao Review. “The credit landscape in China is about to change drastically.”

The revolution is coming, but slowly

The data suggests human lenders in the U.S. are still safe, for the time being. According to the BLS, the number of loan officers will increase 8 percent annually through 2014.

Since the election of Donald Trump, bank stocks have rallied as investors wager that a Republican-controlled government will ease regulations on big financial firms just as rising rates will help boost earnings. Shares of Citigroup, JPMorgan, Wells Fargo and Bank of America have each jumped more than 20 percent since Trump declared victory on Nov. 9.

But as JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon wrote in his letter to shareholders in 2015, “Silicon Valley is coming.”

Here’s one reason. Adyen, a 500-person payments start-up with offices in Amsterdam, San Francisco and 10 other cities, generates more than $1 million in revenue per employee. That looks more like Google than JPMorgan, which is around $400,000 per employee.

Over the last two years, Adyen has been staffing up on data scientists to develop systems for preventing fraud. Adyen’s customers range from Airbnb, Netflix and Spotify to easyJet and NH Hotels. When consumers sign up or make purchases on those apps, Adyen’s software gets to work determining how much it can trust the buyer and whether another form of authentication is needed.

It’s a tricky formula. Asking for more information, be it the answer to a secret question or a code that’s sent to a mobile phone, makes it more likely the consumer will drop off without completing the transaction. Minimizing fraud while maximizing so-called conversions is the goal, and it requires a personalized experience.

Adyen’s engine analyzes the shopper to figure out in real time if it’s a regular customer and if the device, e-mail address and account information are familiar. A trusted buyer can go right through, but any red flags may mean more information is needed.

Sam Halse, Adyen’s chief operating officer, said clients see a 1.4 percent increase in revenue using the software.

“That’s a huge number on the bottom line, which was in the past simply lost revenue,” Halse said.

For Adyen, the algorithm keeps getting smarter, learning more about individual shoppers and broadly how fraudsters behave.

Suranga Chandratillake, a partner at London-based venture firm Balderton Capital, said artificial intelligence in finance represents the next stage of human capital replacement. The first big one was the automatic-teller machine. Then came internet and mobile banking.

Now, it’s what Chandratillake calls “pseudo white-collar jobs,” where machines are being trained to recognize patterns on forms like mortgage applications and insurance claims and to act with better accuracy in less time than people.

“These are jobs that require human judgment but that are very repetitive,” said Chandratillake. “To crack these you need a smart AI founder and team but you also need someone who has expertise in some weird niche like this and can see how to exploit it.”

[Source:-CNBC]