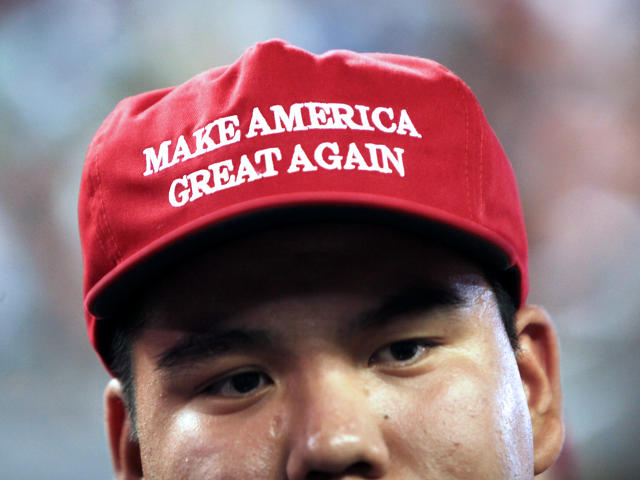

Trump’s ubiquitous bright red trucker hat, festooned with “Make America Great Again,” is now seared into our collective memory. It was the most hated and most loved symbol of the election, the most comical and the most serious. It was a poorly designed product that turned out to be very strong branding. It was the most misunderstood design of the election—for designers and non-designers alike.

But most of all, it’s a lesson about the limitations of “good” design. “No one wants to give [Trump] credit, understandably, because it’s not something that was designed,” says Lindsay Ballant, a designer, art director, and adjunct professor at the Maryland College of Art. “It should be something that designers think about. Good design doesn’t necessarily mean effective design.”

As we move on from the 2016 election and contemplate the role of design in subsequent political campaigns, understanding the difference between good and effective design is imperative.

THE HAT’S ORIGINS

Trump’s slogan itself traces its roots to Ronald Regan’s 1980 presidential bidwhen he ran on a slogan of “Make America Great Again.” Trump applied for a trademark of the slogan in 2012, and it became a registered service mark on July 14, 2015. He first wore the hat during a press conference in Laredo, Texas, just nine days later.

There’s still some mystery surrounding the hat’s genesis. We don’t know who designed it, though we do know where it’s made: In the Southern California factory of Cali-Fame Hats. (The Trump campaign and Cali-Frame Hats did not respond to requests for comment on who was behind the design.) It’s a basic product. More likely than not, someone picked red since it’s the color for the Republican party, and basic Times New Roman lettering in white so it would stand out against the cap.

The New York Times style section called it “an ironic summer accessory” in a September 2015 story. Things would change in the months leading up to the election. The hat took on a life of its own, becoming the subject of memes and parody. It metastasized into a hate symbol and incited violence. It was worn by everyone from an elementary schooler to a Canadian college student and became a free speech flashpoint in both cases.

Expense reports filed to the Federal Election Commission revealed the Trump campaign spent a massive $3.2 million on hats between July 2015 and September 2016. And that sum represents just a fraction of the $15.3 million spent on the collateral category, which includes hats, shirts, and signs. The spending strategy worked, and the hats became ubiquitous.

Yet, when the Trump campaign shared those expense numbers, the media didn’t interpret it as a savvy strategy—it was puzzled and amused. The Washington Post called it a data point that captured the weirdness of the election. Esquire wrote the hats off entirely, arguing that they “may well go down as the Trump campaign’s only lasting contribution to the political history of the Republic. Laugh, clown, laugh.”

It was a joke to many. This rankled documentarian Michael Moore, who saw the jokes and jabs at the hat as the embodiment of a liberal bubble that didn’t understand the Middle American voters who the Democrats were trying to court. Moore appeared on the MSNBC show Morning Joe on November 11 and told the hosts exactly why dismissing the hat and laughing at it showed how Democrats and the media didn’t understand the true gravity of what the hat symbolized to some voters:

I take no pleasure in calling this [election] five months ago. Someone [on this show] was remarking that the Trump campaign spent more money on ball caps that month than anything else. And you panelists were [laughing] ‘ha ha ha ball caps.’ I looked at that and thought, ‘Wow there’s the bubble right there.’ They don’t understand. This is where we’re from. This is where I live. And to make fun of [people wearing the hats]? We wear ball caps . . . This is the reason [Middle America] had this anger at the media and this elitist thing.

Harvard art history professor Sarah Lewis also perceives the hat as a visual symbol of Trump’s appeal, which was misunderstood. “[It’s] a moment that stuck with me on what signals we ignored that are to do with culture that might have given us an indication about how deeply rooted or how animated the demographic Trump was,” she said during a recent WNYC panel, Vision and Justice In Racialized America.

Forest Young, head of design in the San Francisco office of Wolff Olins, tells Co.Design that while the hat is not good design, it is good branding. “Ten years from now, the winning charades team assigned the phrase ‘Presidential Election 2016’ would have simply mimed the motion of someone putting on a baseball cap,” Young says. “The presidential theater here is a play with a single prop . . . Not unlike Yorick’s Skull from Hamlet—the prop of death that symbolically eliminated the differences between people—the illusion of an everyman society was expediently rendered by a billionaire wearing a baseball cap.”

To the thousands of people who wore them to Trump’s rallies and day in and day out in their cities and towns, the hat was a beacon. It was this election’sHope poster. It didn’t make Trump, but it did bolster the persona he was crafting for himself as the candidate for Middle America. He positioned himself as the anti-establishment outsider. It didn’t matter than he was a silver-spoon billionaire afforded every privilege. By destabilizing the system through lies, the truth didn’t matter.

“It’s memorable—even if the implications of what he is saying is terrible,” George Lois told the Los Angeles Times in July 2016. He went on to call the hat “infuriatingly good.”

THE ROLE OF “GOOD” DESIGN IN POLITICS

The “undesigned” hat represented this everyman sensibility, while Hillary’s high-design branding—which was disciplined, systematic, and well-executed—embodied the establishment narrative that Trump railed against and that Middle America felt had failed them. “The DIY nature of the hat embodies the wares of a ‘self-made man’ and intentionally distances itself from well-established and unassailable high-design brand systems of Hillary and Obama,” Young says. “Tasteful design becomes suspect . . . The trucker cap is as American as apple pie and baseball.”

So what exactly is the hat? A stroke of calculated genius or pure dumb luck? There’s no cut-and-dry answer. But it raises the question of how much designerati-approved “good” design really matters in an election.

“This campaign was not won or lost on good design—at least not the kind of design most people are interested in talking about,” says Matt Ipcar, executive creative director at Blue State Digital and a design leader for both Obama campaigns. Referring to the debates designers usually like to have about typography, composition, and color theory, he adds: “We could just as easily be talking about how the Trump hat was an abject failure and how the Pentagram-designed Hillary logo was perfect.”

Hillary’s branding originated from a logo by Pentagram. (Michael Bierut oversaw the process as Wikileaks emails show; Bierut himself has declined to speak about the work.) Her campaign hired Jennifer Kinon, a cofounder of the New York-based firm Original Champions of Design, as its design director and tasked Kinon’s team to build a comprehensive visual system based on the logo. It had many of the same attributes that made Obama’s campaign design successful: clear typography and a polished tool kit that could easily adapt for use on television, the internet, and printed collateral.

Naturally, designers rejoiced at Obama’s visual identity. It reinforced how their principles of good design were successful. “Everyone I know agrees that Obama won the design race,” wrote critic Steven Heller in Designing Obama, a book about the visual identity of President Obama’s campaign. “Whatever the reason, his campaign team knew early on that coordinated graphics were beneficial and this modern typography would signal a change.”

While Hillary and Obama were two fundamentally different people—Obama was a relatively unknown, young senator and Hillary is a seasoned politician with a decades-long resume—they took a remarkably similar tack with branding. To voters who wanted a continuation of Obama’s policy, Hillary’s branding signaled that she would be a successor who would continue the work of her predecessor. Her design team built the campaign visuals to reach—and resonate with—every eligible voter, but it really needed to convince the undecided. In hindsight, it came down to the voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—states where Trump had a razor-thin margin of victoryover Clinton but whose electoral votes were enough to carry him to a national win.

“Maybe [designers] got too high on our own supply from [the Obama campaign] because the branding and approach was so different,” Ballant says. “It all goes back to the idea that I now understand as the creative class as an extension of the professional class and the bubble that exists . . . we’ve blocked ourselves off and we’re not talking to anyone else outside of that. Or we assume there’s enough of us in that we can prevail and it’s not true anymore.”

Ballant reiterates that Obama and Hillary’s campaigns were rooted in corporate identity design and points out that corporations aren’t very popular right now. “Hillary’s branding felt too corporate,” she says. “But that also reflected an entrenched reputation she had to push against. And the design, while very good, unfortunately only served to reinstate that fact, especially when you think of how big of a deal it was when the logo was unveiled. It was treated like a Mastercard, Airbnb, or Uber reveal.”

While Trump’s sloppy branding and (suggestive) logo were written off by the design community as a sign that his campaign didn’t know what they were doing, in hindsight it was likely more deliberate than originally thought.

“Like any good confidence man, Trump was highly aware of his audience’s desires,” Ipcar says. “Take a look at trumphotels.com. His people understand clean and sophisticated branding; they just chose not to use it for his campaign. There was a clear decision by Trump or someone on his team to make the campaign look like something completely different. It was easy for me, as a Brooklyn-born creative director, to describe the hat as bad design. But the hat was worn. It was simple, unisex, familiar, and practical during a summer of hot crowded rallies throughout the South. Design-wise, it was lazy and loud, but also deceptively brand-aware and unmistakably Trump—a brash and calculated brand extension for a house whose luxury properties are awash in Gotham, understated bling, and lots of white space.”

The 2016 campaign revealed limitations of what “good design” can achieve as a communication tool in a political context. “Good design has an elitist bias, particularly because good design is expensive,” Ballant says. The role of designers in a political context when capital-d Design is so suspect is no less important, but it will take some retooling.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR DESIGNERS?

In October, Ballant presented a lecture to the AIGA NY, which Matt Ipcar moderated, about what design can and can’t do in the context of an election. During her talk, she drew parallels between the presidential campaign and the United Kingdom’s “Brexit” vote to leave the European Union, and referenced an article London-based Pentagram partner Marina Willer wrote for Eye. In the piece, Willer expressed guilt about what designers weren’t able to accomplish.

It’s not that our industry was silent. Many campaigns were crafted for the Remain camp and many things were said. We created clever campaigns, beautiful campaigns, and funny campaigns, but we created them for each other, myself included. By and large we preached to the converted, when what we needed to do was to give those who were undecided some clarity. To change history we needed to directly speak to those who chose to vote leave by communicating simple information and direct implications.

Ballant found herself wondering about what can happen when design isn’t overthought or overproduced with the hat as a prime example. “The making of the hat, the actual idea of it, might have come from a brand strategist or it might not of, which is kind of the salient point,” she says. “It certainly wasn’t a ‘design first’ strategist or thinker. It didn’t come from a team of design experts. It’s not slick. Its origin seems spontaneous, not thought out. It seemed like it was a one off made on a whim, without any thought as to how it operated within a larger system, or without any expectations as to what its impact was or what system it built off of. It didn’t seem like it came from a pitch deck. It was, like Trump, sheer personality.”

While Ballant is far from calling for a revolt against design systems and style guidelines, she advocates a broader tool kit for designers. “In a way, the fluke success of that hat was a rejection of ‘design thinking’ and ‘design strategy’ as a whole,” Ballant says. “And designers should really think about that, because we’ve built a whole economy around that as a practice. We’ve sold ourselves on the premise that this is how things should be done.”

She argues sometimes it might be strategic for designers to ignore instincts about the visual aspects of design—like kerning, typography, and a systematic polished sensibility—and embrace an “undesigned” approach since it might be more relevant or effective in certain situations. “Hillary’s direction was universally praised as good design,” Ballant says referring to the sophisticated direction Hillary took. “The pundits were all wrong, the pollsters were wrong, and the design class was wrong, too.”

A couple months ago in Central Park, well before the election, I saw three women who were clearly out-of-towners and who looked like they had just come from the Trump store, judging from the crisp Trump shopping bags they had in tow. They were wearing the Make America Great Again caps and, as tourists do, were snapping photos in the park. As I saw it, to them, a pilgrimage to the Trump store was as much of a not-to-miss attraction as Central Park. I, too, underestimated the gravitational pull Trump’s hat had to his most fervent supporters, and to voters who were were looking for a candidate who could inspire the type of hope they wanted. While Hillary won the popular vote by a landslide—the latest count puts her at 2.8 million votes over Trump—she just didn’t come out ahead in the states where she needed Electoral College votes the most. It was the people who would venture to N.Y.C. to shop at the Trump store that Democrats had to convince, and unfortunately, they weren’t able to.

The 2016 election probably wasn’t won or lost on a hat or a branding system, but the hat serves as a powerful proxy for how blindsided many were by the forces that led to Trump becoming president-elect. It’s an allegory about how to interpret symbols, how to deploy design, and why visual fluency is crucial for everyone—not just designers—as we process, regroup, and strategize for the next round of elections.

[Source:- Co Design Blog]