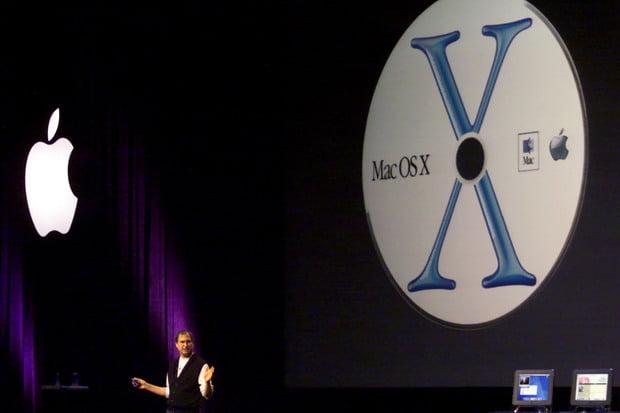

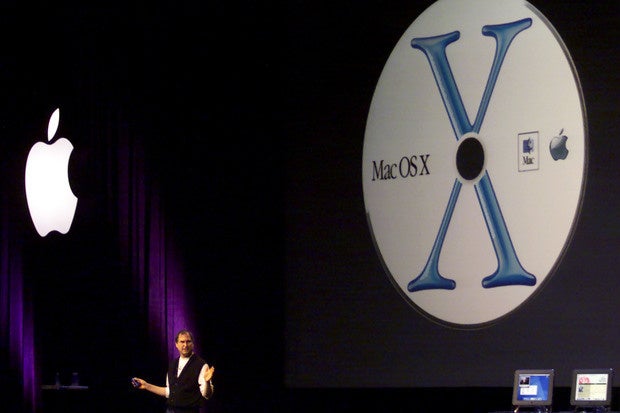

Although OS X is now an integral part of the Mac experience, it represented a big gamble for Apple when the first general release version — code-named Cheetah — arrived on March 24, 2001. It was also a gamble that Apple had little choice in making — and one that has paid off in the 15 years since, becoming, directly and indirectly, one of the critical factors in Apple’s success.

Still, there were many points at which things could have gone awry and decimated the company.

The road to OS X

The road to OS X’s initial release was a very bumpy one. Even before there was any thought of Apple buying NeXT, thus returning its CEO, Steve Jobs, to the company, Apple executives faced challenges with what was then thought of as the classic Mac OS.

The original Mac OS may have been revolutionary when it was unveiled in 1984, but it wasn’t designed with many features that modern operating systems would need. Initially, it offered no ability to multitask, although “cooperative multitasking” could allow a single app to monopolize the processor. There was no protected memory, meaning that if one app crashed it would likely take others down with it and potentially the entire OS. And aside from a little-known product called At Ease aimed primarily at education, it offered no support for multiple user logins.

All these challenges were becoming obvious by the early 1990s, prompting Apple to devise a strategy to create a next-generation OS. The primary focus was an internal project called Copland, announced in 1994. After significant delays, Apple’s then-CTO Ellen Hancock and CEO Gil Amelio froze development of Copland as a successor OS in 1996. Several parts of the project were pushed into the development of Mac OS, but they were more useful add-ons than core architectural changes.

Apple then began looking for other companies that could supply a base for a future Mac OS. Multiple options were reportedly considered, including Windows NT, Sun’s Solaris and a nascent computing platform called BeOS — the last one created by Be, a company founded by former Apple exec Jean Louis Gasse. Be seemed the clear favorite, but as negotiations dragged on, Apple got a call from NeXT. Jobs returned to the Apple campus for the first time in over a decade and presented NeXT’s OS as a fully functional and modern platform that was years ahead of BeOS.

In what struck many as a surprise move, Apple acquired NeXT and the real journey to OS X began. (For an excellent retelling of this saga, check out Owen Linzmayer’s Apple Confidential.)

The risks of OS X

Apple faced three major challenges in transitioning its core product line to a completely new OS, whether it was developed internally or by acquisition. The first was getting the new OS out the door quickly. Apple was in dire straits in the mid-’90s and was losing market share to Microsoft. It needed a quick win. That led to the second challenge: Keeping developers engaged enough to write or rewrite apps for a new platform, something made more challenging by Copland’s delays and cancellation. Finally, Apple needed to convince its user base to adopt the new OS.

Appealing to Apple users was crucial, as attracting new users would likely get harder over time. Those die-hards also had different wants, needs and agendas.

- General consumers would want a new OS that still felt like the Mac experience they’d grown to know.

- Professional users, mostly in media and other creative fields, needed performance, reliability and interoperability with the apps and peripheral devices they used.

- And power users and technicians that understood the classic Mac OS inside and out would need to be able to troubleshoot its successor and modify it as needed for their personal needs or the needs of their employers/clients. (Being part of that last group, I was among those most skeptical at the time).

The main reason Apple needed this buy-in was that OS X was designed to be the single future OS. Although Apple didn’t need everyone to migrate on day one, it did need for everyone to do so eventually.

Rhapsody, OS X Server 1.0 and the OS X public beta

The initial effort was called Rhapsody; it involved an environment that ran the new OS (known as the Yellow Box) and the ability to run existing Mac apps (the Blue Box). Apple released two developer previews of Rhapsody, but after Jobs retook the reins of the company, the new OS was rebranded as Mac OS X (later OS X). The Blue Box concept survived as the “Classic environment” in early OS X releases; it essentially ran a version of Mac OS 9 inside OS X as though it were an app or OS X process.

Before OS X arrived in consumer form, the first beta version of a server OS for education and enterprise environments called Mac OS X Server 1.0 was released. It supported services like file sharing, Mac management and booting from a shared network image rather than a physical drive (useful in education and kiosk environments). This initial release wasn’t like any later version of OS X (or OS X Server). It was essentially a version of Rhapsody and was very much a mashup of NeXT’s OPENSTEP and Mac OS 8.

In the fall of 2000, the public got its first look at the consumer version of OS X — as a $29.95 public beta. Although Apple has a penchant for presuming it knows what users want before they do, the company made an exception to that rule in this case and feedback about the beta did inspire changes in some of OS X’s user experience. The most notable tweak was the continued existence of the Apple menu, which wasn’t present in the beta.

Mac OS 9 and Classic

Mac OS 9, released while OS X was already in development, served as an important bridge between the two operating systems. While it didn’t introduce any of the core architectural changes Apple needed, it did add support for multiple user logins, including network accounts; a basic level of Mac management; and the underpinnings needed for it to function as an OS X process as part of the Classic environment.

Cheetah arrives, then Puma

The first commercial release of OS X, code-named Cheetah, went on sale for $129. It wasn’t an immediate hit. There were issues with performance, many users experienced kernel panics that could require a forced restart, features like burning CDs and DVDs weren’t supported and there was a dearth of available printer drivers.

Simply put, Cheetah didn’t seem ready for prime time.

Complicating the matter was a lack of native apps beyond those bundled with the new OS. Because launching the Classic environment essentially fired up Mac OS 9 after OS X had already booted, many users simply opted to boot into Mac OS 9 to use the majority of their apps.

The situation improved that fall with the release of Puma (OS X 10.1). Puma didn’t add a huge number of features, but it did improve performance and stability. The features it did roll out, however, were significant to developing confidence in OS X: CD and DVD burning, DVD playback, drivers for 200 printers, and the Image Capture utility for accessing digital cameras and scanners. Apple released Puma free of charge to Cheetah users and offered the upgrade through its traditional sales channels as well as in its new retail stores, where people could get help with the transition from Mac OS 9 to OS X.

Puma’s ability to rectify Cheetah’s limitations was important, given that early in 2002 Apple announced all new Macs would ship with OS X pre-installed as the default operating system. Although this crop of Macs could still boot into Mac OS 9, it was clear that Mac OS 9 was on its way out.

[Source:- Computer world]