Andy Warhol’s New York loft on East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan, called the Silver Factory because every surface was embellished with aluminum foil and silver paint, was to the social life of postwar art what Gertrude Stein’s Rue de Fleurus apartment in Paris or the Royal Academy of Art’s drawing rooms in London were to previous eras.

But the Silver Factory wouldn’t have been the hallowed salon it was had Warhol, in 1959, not run into a handsome, brooding waiter named William Linich Jr., a refugee from the middle-class straits of Poughkeepsie, N.Y., who had moved to the city and plunged into its ferment as the Beat years gave way to the counterculture.

When Warhol later went to get a haircut at Mr. Linich’s apartment, he was so wowed by its obsessive reflective décor (“I even painted the silverware silver,” Mr. Linich once recalled) that he invited Mr. Linich uptown to decorate the loft the same way — an act that came to symbolize an entire Pop worldview that Warhol would invent.

In the book “Popism: The Warhol Sixties” by Warhol and Pat Hackett, Warhol wrote of the man who later rechristened himself Billy Name, “Why he loved silver so much I don’t know. But it was great. It was the perfect time to think silver.” It was the future, he said, the space age, and also the past, the silver screen and old Hollywood. “Maybe more than anything,” he added, “silver was narcissism — mirrors were backed with silver.”

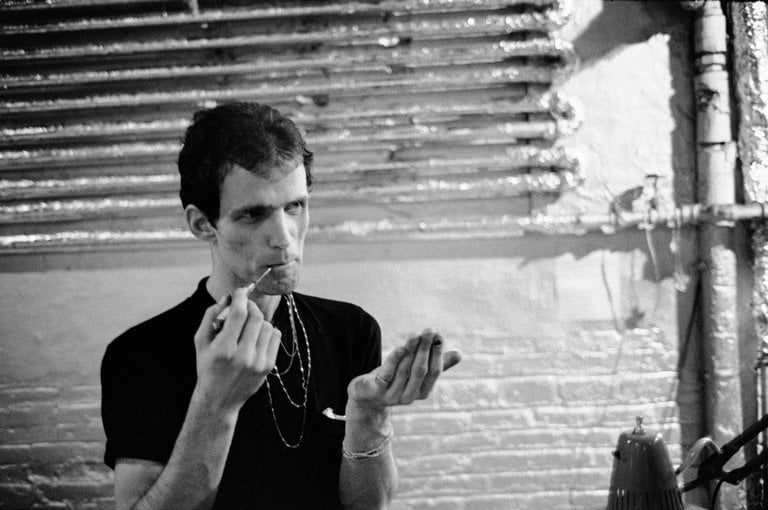

Billy Name, who became Warhol’s lover, muse and court photographer, leaving behind a monumental visual record of the 1960s art world in and around the Silver Factory, died in Poughkeepsie on Monday at 76. His agent and executor, Dagon James, said the cause was heart failure.

After leaving Warhol’s orbit in 1970, Mr. Name spent a decade in San Francisco before moving back to Poughkeepsie.

His photographs — he took thousands, in a moody, high-contrast black and white — did more than just capture Warhol’s retinue, his “superstars”: Edie Sedgwick, Brigid Berlin, Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez, Mary Woronov, Ondine, and Bibbe Hansen. They also documented the larger scene around the Factory, including fellow artists like Ray Johnson, Jasper Johns and John Cage; the members of the Velvet Underground; the filmmaker Barbara Rubin; and admirers like Bob Dylan and Salvador Dalí.

“It’s odd when the past looks so much like the future,” the editor Glenn O’Brien, a Factory denizen, wrote about the images in “Billy Name: The Silver Age,” a collection of Mr. Name’s work published in 2014. Warhol, he added, “never looked better than he did in these silver pictures, surrounded by all the beauties — shining like a full moon in their reflected light. I don’t suppose the night ever looked better than it did right then.”

William Linich Jr. was born in Poughkeepsie on Feb. 22, 1940, the son of Carleton Linich, a barber, and the former Mary Gusmano. He moved to Manhattan in 1958 and, besides waiting tables and cutting hair, worked as a lighting designer for the Judson Dance Theater and other theater spaces.

Information about survivors was not immediately available. Mr. Name was estranged from his family.

The Factory, whose name he helped invent, became his workplace and spartan home not long after Warhol gave him a 35-millimeter Pentax camera. He refashioned a bathroom into a darkroom and bunked near it, with hangers for his few clothes, a turntable and a collection of opera records. Introverted and practical, he was in many ways Warhol’s alter ego, and he served as the Factory’s unofficial foreman and manager.

“He was quiet, things were always very proper with him, and you felt like you could trust him to keep everything in line, including all his strange friends,” Warhol wrote, adding: “If Billy said, ‘Can I help you?’ in a certain way, people would start to actually back out. He was a perfect custodian, literally.”

But Mr. Name’s stability was always fragile. Under the strain of amphetamines and other drugs, it began to shatter not long after Warhol was shot in 1968 by the radical writer Valerie Solanas, in a new Factory iteration on Union Square.

Mr. Name spent months afterward in hermetic solitude, rarely emerging from his room during the daytime. In 1970 he moved out of the Factory for good, leaving a note that said only: “Andy — I am not here anymore but I am fine.”

But he wasn’t fine. The poet Diane di Prima, with whom he stayed in Los Angeles after leaving New York, said: “He was completely out of his mind. He read the same page of the same book for several months: Page 37 of ‘Esoteric Astrology’ by Alice Bailey. He would see things in the air and he would catch them. This went on for months and months.”

In San Francisco he spent most of his time studying Buddhism and writing concrete poetry. He never reaped any financial rewards from his days at the Factory.

A large archive of his 1960s negatives disappeared several years ago and has still not been recovered. He said that Warhol gave him paintings, including a triptych of silk-screened images of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, works that probably would have come to be worth tens of millions of dollars. When Mr. Name left New York, he gave his things to the curator Henry Geldzahler for safekeeping; Mr. Geldzahler later told him that the Warhol superstar Paul America, in need of money for drugs, broke into his apartment and stole the paintings.

But Mr. Name, who seemed to live on a slightly different plane than those around him, never cared much about worldly possessions. “We all loved Billy,” John Cale, a founder of the Velvet Underground, once wrote. “We all missed him those times he’d retreat but said little, thinking he was due the deference to work out whatever demons were invading his head.”

[source:- Art & Design]