Throughout Asia, ink wash painting on rice paper has been a popular artistic medium for hundreds of years. Historically, it was often used to portray idyllic landscapes and other scenes of nature, because the way the ink diffuses through the paper lends itself to a dreamy style. Since the late 20th century, this same ethereal quality has inspired artists in China and South Korea to use the medium to create more abstract works.

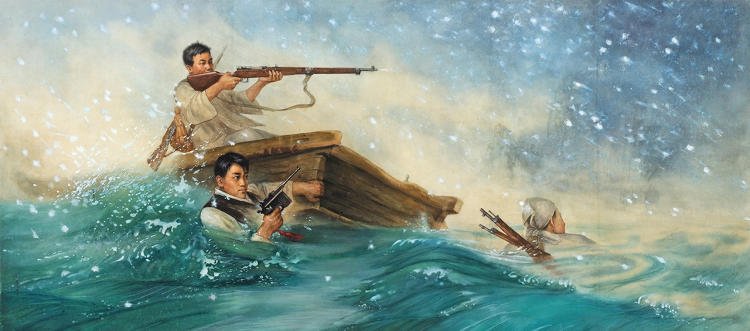

In North Korea, this style of painting is called choshonwha. But about 50 years ago, when China finally withdrew from the country, something interesting happened with choshonwha. Locked behind North Korea’s impenetrable borders into an artistic universe by itself, choshonwha painting has evolved over the last 50 years into a fascinating genre of highly detailed propaganda painting, now being showcased as part of a new exhibit, Contemporary North Korean Art: The Evolution of Socialist Realism, at the American University Museum in Washington, D.C.

Curated by Korean-American artist and art historian B.G. Muhn, Contemporary North Korean Art highlights 50 years of choshonwha paintings, and introduces it to the West, largely for the first time. “North Korean art is the last form of socialist realism painting in the world,” Muhn tells me. “Because their society has been closed off for 70 years, the style of art they do is completely different from artists in other countries working in the same medium.” But what is choshonwhapainting, and how does it differ from similar genres in other countries?

First, Muhn says, North Korean choshonwha artists tend to do realistic work. The paintings are extremely detailed, and while those details are often glorified or idealized, North Korean artists spend a great deal of time trying to make sure their art looks like things as they exist in the real world. That isn’t to say that North Korean artists indulge in photo-realism, though. “They hate that,” explains Muhn. “They don’t consider photo-realistic paintings to be art. It’s too slick for North Koreans’ tastes. It needs to have human touches.”

Besides the obvious propaganda bent of many of the works, another distinction between North Korean choshonwha and ink wash rice paintings is literalism. “In North Korea, the goal of art is the same as everything else in a socialist society: It exists to serve the people,” Muhn explains. “That means every painting needs to be something that anyone can understand.” So if you see a tiger in a North Korean painting, it isn’t symbolic of anything, like—say, the indomitable spirit of the North Korean people. It’s simply meant to be a literal tiger. “I don’t think there’s any symbolism in North Korean art,” Muhn says matter-of-factly.

Another way that choshonwha differs from similar forms is the way it’s produced. Every spring and fall, North Korea mobilizes all of the country’s artists to document aspects of the country’s life as the season changes, from the fields to the factories. From a Western perspective, it sounds strange, but Muhn says North Koreans consider this their civic duty. “In a socialist society, ideally, everything is collected from the people, and then it’s distributed equally,” he says. In that sense, art is like anything else in North Korea: Like a crop, it’s harvested by the season.

For these reasons, along with their relative rarity, choshonwha paintings have become increasingly valued by collectors over the years—so much so that Muhn tells me that there are entire forging workshops in southern China devoted to manufacturing the paintings.

Muhn says that most of the paintings in his exhibition were procured through the Mansudae Art Studio, the famed Pyongyang art production center which mass-produces art and employs half of the country’s artists. Visiting there, Muhn says,choshonwha paintings can be procured for anywhere between $100 and $1,000 each. “Most of it’s pretty kitschy, though,” admits Muhn.

Contemporary North Korean Art will be on view at American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, D.C., until August 14.

[Source:- Co design blog]