A Chicago company has marketed a tool using text, photos and videos gleaned from major social media companies to aid law enforcement surveillance of protesters, civil liberties activists say.

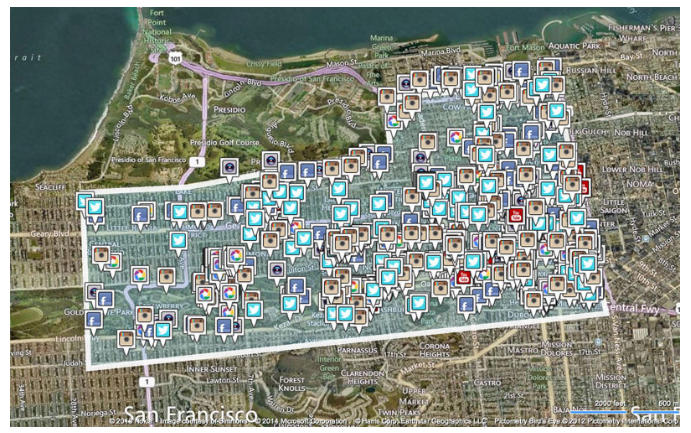

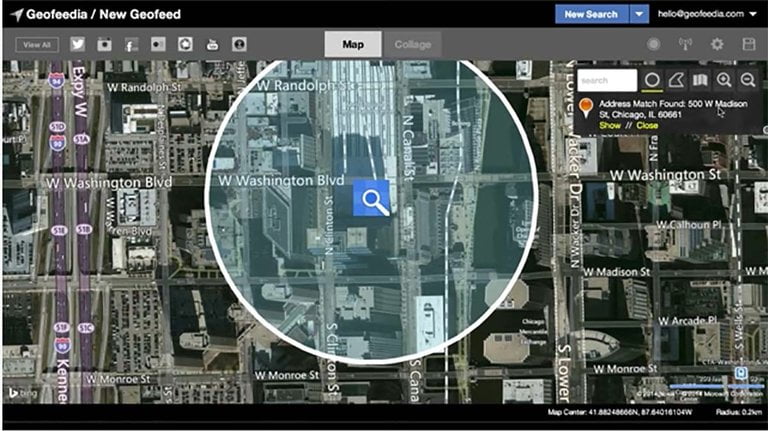

The company, called Geofeedia, used data from Facebook, Twitter andInstagram, as well as nine other social media networks, to let users search for social media content in a specific location, as opposed to searching by words or hashtags that would be less likely to reveal an exact location.

Geofeedia marketed its abilities to law enforcement agencies and has signed up more than 500 such clients, according to an email obtained by theAmerican Civil Liberties Union. In one document posted by the organization, as part of a report released on Tuesday, the company appears to point to how officials in Baltimore, with Geofeedia’s help, were able to monitor and respond to the violent protests that broke out after Freddie Gray died in police custody in April 2015.

Geofeedia appears to have used programs that Facebook, Twitter and other social media companies offered that allow app makers or advertising companies to create third-party tools, like ways for publishers to see where their stories are being shared on social media.

Facebook, Twitter and Instagram say they have cut off Geofeedia’s access to their information. But civil liberties advocates criticized the companies for lax oversight and challenged them to create better mechanisms to monitor how their data is being used.

“These platforms should be doing more to protect the free speech rights of activists of color,” Matt Cagle, a lawyer with the A.C.L.U. in Northern California, said in an interview. “When they open their feeds to companies that market surveillance products, they risk putting their users in harm’s way.”

Instagram and Facebook terminated Geofeedia’s access to their data in September, while Twitter shut off access on Tuesday. The response from the companies suggested that Geofeedia was using data from the companies in a way that was not allowed under their developer agreements.

Jodi Seth, director of policy communications at Facebook, said that Geofeedia had access to data that had been made public on the social network, and that access was subject to the limitations in its platform policy. That policy asks developers to “provide a publicly available and easily accessible privacy policy that explains what data you are collecting and how you will use that data.”

It also asks that they “obtain adequate consent from people before using any Facebook technology that allows us to collect and process data about them.”

Twitter said that based on the information found by the A.C.L.U., it was “immediately suspending Geofeedia’s commercial access to Twitter data.”

Phil Harris, chief executive of Geofeedia, said in a statement that his company “provides some clients, including law enforcement officials across the country, with a critical tool in helping to ensure public safety while protecting civil rights and liberties.” He said the firm has policies to prevent “inappropriate use of our software.”

Mr. Harris added that the company understands that given how quickly digital technology changes, Geofeedia “must continue to work to build on these critical protections of civil rights.”

In addition to law enforcement agencies, the company has marketed its services to journalists as a way to find people at breaking news events for interviews and social media content. The New York Times used Geofeedia on a trial basis, but has not had access since 2015.

The A.C.L.U. said it first learned about the agreements with Geofeedia from responses to public records requests to 63 law enforcement agencies in California. Those records, the organization said, revealed a significant expansion of social media surveillance.

“Posts on social media platforms can reveal information about our location, our religion, the people we associate with,” Mr. Cagle said. “Users of social media websites do not expect or want the government to be monitoring this information. And users should not be at risk of being branded a risk to public safety simply for speaking their mind on social media.”