Abstract

Currently, a full appreciation of how problem gaming impacts the daily lives of gamers is lacking. This study aims to gain a more holistic understanding of the activities in the daily lives of problem gamers; particularly, what is important to them, what motivates gaming, and what supports/constraints engagement in other life activities. Semi-structured interviews and week-long activity logs were used to collect data from the 16 problem gamers in five countries. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically. Two main themes emerged. First, gaming was found to be a meaningful and purposeful activity. Participants in this study understood what activities offered them a sense of meaning and personal growth. Video gaming offered both positive and negative experiences in gamers’ lives. The negative experiences mainly resulted from using video games as a coping strategy for other life stressors. Second, individual, interpersonal, and environmental influences acted simultaneously to push and pull on the amount of gaming. The push and pull influences on the amount of gaming can occur in real-life or virtually. Assistance for problem gamers could include minimizing/removing the pull forces and obtaining adequate push forces to enable their desired participation in daily activities.

1. Introduction

The popularity of playing video games has grown immensely over the past decade. Approximately half of Americans play video games on various electronic devices while 10% of those who play self-identify as being a gamer (someone who consistently plays video games and identifies with the gaming community) (Pew Research Centre, 2016). A growing body of research has found positive uses for video games (Ferguson, 2010), including reducing flashbacks from posttraumatic stress disorder (Holmes, James, Coode-Bate, & Deeprose, 2009), reducing chronic pain (Jones, Moore, & Choo, 2016), and training of health care professionals (Wang, DeMaria, Goldberg, & Katz, 2016). They have also been found to support student learning by stimulating their engagement in field observations (Hwang & Chen, 2017), improve visual-spatial cognition (Spence & Feng, 2010), arithmetic, memorization, leadership, and team functioning (Thirunarayanan & Vilchez, 2012). However, it is also known that problems may arise when video game playing is excessive. In Canada, a survey study using the Problematic Videogame Playing Scale (Tejeiro Salguero & Moran, 2002) found that 9.4% of adolescent gamers experience problematic gaming with 1.9% being described as having severe problems (Faulkner, Irving, Adlaf, & Turner, 2014; Turner et al., 2012). Although there is an ongoing debate regarding the inclusion of gaming disorder in the ICD-11 (van Rooij et al., 2018), it is generally understood that problem gaming is not necessarily “addicted” gaming.

Problem gaming can be defined as a persistent and recurrent involvement in video gaming that results in psychological distress and functional impairment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Shapira et al., 2003). Recent longitudinal studies demonstrated conflicting views of the stability of problem video gaming. A 3-year longitudinal study conducted among adolescents in Sweden found problem gaming to be relatively stable over time (Vadlin, Aslund, & Nilsson, 2018). A 5-year longitudinal study among adults in Canada had contradicting findings from Vadlin et al. (2018) where it found problem gaming be transient for most gamers (Thege, Woodin, Hodgins, & Williams, 2015). Furthermore, a correlational panel study of German adolescents also found that excessive gaming is often episodic in that it may appear and disappear quickly from one’s life (Rothmund, Klimmt, & Gollwitzer, 2016).

Gamers have been found to play for a variety of reasons. In a qualitative study, Snodgrass et al. (2014) found problematic play was a response to life stress where using video games excessively was a diversion that lead to problems. In a survey of non-problem MMORPG gamers, Yee (2006) found three overarching motivations—achievement, immersion, and a social component. Other studies with a small percentage of problem gamers found escapism/coping, mechanics, a social component, experiencing fantasy, and obtaining in-game wealth/achievements were motivations to gaming (King, Herd, & Delfabbro, 2018; Kuss, Louws, & Wiers, 2012; Laconi, Pires, & Chabrol, 2017). Although several studies have examined gaming motivations, few have intentionally sampled only problem gamers to obtain first-hand accounts.

1.1. Gaming as “occupation” and impact on function

Occupations are everyday activities that people engage in that bring meaning and purpose to life (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2016). Humans are naturally occupational beings who need to use time in a meaningful and purposeful way (Wilcock, 1993). These activities contribute to identity, motivation, and routines (Wasmuth, Crabtree, & Scott, 2014). The activity of gaming has been described by gamers as fun and meaningful activity (Rogers, Woolley, Sherrick, Bowman, & Oliver, 2017). It is particularly important to have activities in life that offer choice and control to prevent occupational deprivation (or boredom) (Townsend & Polatajko, 2013, pp. 71–80). Boredom is a lack of engagement in meaningful activity and consequently a lack of function.

Function is described as a feature of gaming disorder in the ICD-11 and the DSM-V (APA, 2013; World Health Organization, 2017). The importance of functional impairment has also been highlighted in recent debates regarding the disorder (Billieux et al., 2017). Studies have demonstrated that functional impairment is present in problem gamers. Functional impairment was also emphasized by gamers in a mixed-methods study conducted at a video game convention in the USA, in which gamers agreed that functional impairment was the top sign of problematic gaming (Colder Carras et al., 2018). Among the functional issues reported were: neglecting their own needs/responsibilities and a loss of interest in previous hobbies/activities (Colder Carras et al., 2018). Several other studies have identified productivity issues at work and school (Cole & Griffiths, 2007; Gentile, Lynch, Linder, & Walsh, 2004; Hastings et al., 2009; Hellström, Nilsson, Leppert, & Slund, 2012). Although the implications of functional impairment in activities relating to gamers’ lives have some very practical repercussions and are directly related to well-being, directly addressing function through the examination of daily activities has generally not been the focus of research studies.

1.2. Thematic anchors and study aims

Qualitative research focuses on obtaining an in-depth understanding of a specific set of experiences with in real-world contexts (Creswell, 2009; Mays & Pope, 2000). Hence, the social ecological model as a guiding model for this study demonstrates excellent compatibility with a pragmatism worldview that was used to guide this study. The social ecological model provides a holistic conceptual framework that human behaviors, environmental conditions, and well-being are inter-related (Stokols, 1996). Applied to problem gaming, it proposes that the forces underlying the problem are not solely based in the individual gamer but also on the interrelationships between the gamer and his/her surroundings.

Examining factors outside of the individual found reciprocal relationships within family dynamics where poorer parental relationships were associated with increase problem gaming and long-term problem gaming had negative effects on the family (Schneider, King, & Delfabbro, 2017). Furthermore, a systematic review of longitudinal trends with those who experienced Internet use and problematic Internet use examined issues occurring at the individual, peer, family, and classroom levels (Anderson, Steen, & Stavropoulos, 2017). This study found an interplay between these internal and contextual factors that moderate and individual’s engagement in Internet use. However, such studies group gaming with other Internet-related activities such as social media use and online gambling. Snodgrass et al. (2014) used a culturally-sensitive approach that found that problem gaming is on a continuum with positive play experiences.

The social and environmental forces associated with problem video gaming need to be considered in combination with individual ones to reveal a more complex picture of problem video gaming that the current literature has not yet captured. Currently, a full appreciation of how problem gaming impacts the daily lives of gamers is lacking. Moreover, there has been a lack of studies that focus on functional activities and aim to examine first-hand accounts from problem gamers without bias from non-problem gamers. The aim of this study is to gain a more complex understanding of the activities in the daily lives of problem video gamers, particularly: 1) What activities are important to them? 2) What motivates gaming? 3) What supports/constraints to engagement they experience in other life activities?

2. Method

This study employed a qualitative thematic approach using semi-structured interview and activity logs. The themes arose from the data collected about the experiences of PGs (Boyatzis, 1998). Ethical approval was obtained at authors’ institutions. Participants were recruited through recruitment posters posted throughout a mental health center serving a large geographical area, and advertisements on a stakeholder listserv, online gaming treatment websites, and gaming-related forums. Snowball sampling was used (Noy, 2008). Interested participants were included if they were people who: played video games, were at least 16 years old, scored five or more out of nine questions on the Problem Videogame Playing Scale (PVP) (Tejeiro Salguero & Moran, 2002), did not play mostly gambling games, and did not play games professionally/train with professional gamers. A score of more than five on the PVP indicates the presence of problem gaming (Cronback’s alpha at 0.69) (Tejeiro Salguero & Moran, 2002).

Informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to each interview. Eligible participants were asked to keep a daily activity log on an hourly basis for one week (Appendix A). Activity logs are a method to examine daily activity patterns and help individuals be more aware of how time is spent (Willard & Schell, 2014, p. 170). They were used to help increase the accuracy of self-reporting and for comparing participants’ perceptions of their time use to what they were actually doing. The logs also helped provide additional insights into their daily lives and stimulate discussion during the interview. Participants were asked to bring or email their logs to the interviewer for the day of the interview. Semi-structured interviews and probes were used to understand the experiences of PGs. The semi-structured interviews were approximately one hour long. They were conducted either in-person, by phone, by Skype video, or by Skype audio only (Appendix B for interview questions). The interviewer (first author) attempted to bracket prior experience with video games during the interviews by allowing participants to expand on their description of gaming related features and used probing questions to facilitate detailed descriptions from the participants. Interviews and data analysis were conducted concurrently through an iterative process. Interview questions were modified as data were collected to gain a better understanding of gamers’ lives (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Data collection through interviews continued until theoretical saturation was reached. This took place between December 2016 to June 2017.

2.1. Data analysis and rigor

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and analyzed thematically using methods suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis is particularly useful at investigating new, under-explored areas, or participant perspectives that are yet to be uncovered (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It is also a useful method to gain a rich understanding of people’s experiences. Data analysis was inductive in that themes were created from the codes and that categories emerged from the data. This was a systematic process of organizing and presenting data in ways that allowed the identification of connections, patterns, and categories (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003).

Computer-aided qualitative data management software NVivo, Version 11, 2015 by QSR International Pty Ltd. was used. The first author and the last author individually coded two transcripts to support data analyses and triangulation. The first author coded all remaining transcripts. The interviews, together with the logs, are a form of methods triangulation where findings are generated by different data collection methods (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Finally, reflexive memos and analytic notes were taken after interviews and during the transcribing phase. Reflections and analytic thoughts were also discussed with colleagues throughout the research process.

2.2. Participant characteristics

Sixteen participants (11 male; 5 female) aged 16–35 years old were interviewed for this study. Their mean score on the PVP was seven out of nine. According to their activity logs, the participants played a mean of 30.85 h of video games per week, ranging from 10 h to 62.5 h per week. Three people did not fully complete the activity log and were excluded from the calculations. However, actual gaming hours may have been higher due to interview reports that: 1) they were gaming while performing other activities, 2) missing data in logs may have been time spent gaming and, 3) two participants were travelling during the time of log completion so it was not a typical week. Furthermore, time spent on other gaming related activities that did not involve physical game-play from the participants were also not included in the mean hours per week calculation. These gaming-related activities included: 1) watching others play via live streams, 2) reading strategy guides, 3) reading fan-fiction, 4) thinking about games, and 5) fixing/building a computer. Table 1 provides a summary of participant characteristics.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| Participant Characteristic | n = 16 | |

|---|---|---|

| Country of participant | Canada | 7 |

| USA | 6 | |

| Peru | 1 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 | |

| Japan | 1 | |

| Mode of Interview | In-person | 4 |

| Skype Video | 8 | |

| Skype Audio Only | 3 | |

| Phone | 1 | |

| Vocation | Schoola | 7 |

| Workb | 8 | |

| Unemployed | 1 | |

- a

-

Full-time or part-time school (secondary education or higher); some students also worked part-time hours.

- b

-

Full-time or part-time work.

3. Findings

Two main themes emerged from interview data analysis—gaming as meaningful and purposeful and push-pull influences on the amount of gaming, each with sub-themes (Table 2). The first theme pertains to the meaning, purpose, and roles that gaming serves in a person’s life. The second theme describes different forces that influence decision-making about engaging in gaming versus other activities in life. Verbatim quotes from interviews are presented to support the themes. Pseudonyms are used to preserve anonymity of participants.

Table 2. Summary of themes and sub-themes.

| Themes | Sub-themes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gaming as meaningful & purposeful | Gaming as a part of life | Gaming has always been a part of their lives and is integrated into their lifestyles. |

| Gaming community as a sub-culture | Gamers are part of a network of people who share similar interests and experiences through video games. Outsiders of this sub-culture might misunderstand gamers or have a lack acceptance for playing video games. | |

| Gaming as a purposeful activity | Playing video games fulfills a purpose in their lives. This could include gaming for: relaxation, opportunities to exert control, enjoyment, creativity, socialization, prevent boredom, challenge, and achievement. It could also be used as a coping method or stress management. | |

| Push & Pull influences on the amount of gaming | Personal influences | Influences that are within the control of the individual or are a characteristic of the individual, such as: their sense of responsibility for other tasks and roles, ability to plan/schedule, and meet self-care needs. |

| Interpersonal influences | Influences from those who interact with the individual, such as: co-habitants, friends, social apps/websites, co-workers, teammates, and therapists. | |

| Environmental influences | Influences that are typically outside of the control of the individual, such as: design of the games, where they live, and environmental supports/constraints on activity engagement (online and offline). |

3.1. Theme 1: Gaming as meaningful & purposeful

Participants revealed that playing video games is a meaningful and purposeful activity, and that it holds a place in several facets of participants’ lives. For example, friendships are formed around games, it is something they enjoy, some want to work in the video games industry in the future, and they spend time thinking about games. This section will discuss the subthemes relating to gaming as a meaningful and purposeful activity: gaming as a part of life, the gaming community as a sub-culture, and the role gaming fulfills in a gamers’ lives.

3.1.1. Gaming as part of life

Adam’s quote was his response to being asked about whether he feels like he needs to cut down on gaming. Interestingly, all participants reported having grown up with video games as children where a family member encouraged them to play or they watched a family member play. Having grown up with video games, participants felt that gaming is part of who they are and a part of their lives.

Gamers reported that they integrated gaming into their lifestyles. Gaming offers a way to fill idle time but also provides them with a sense of “doing” and engages them with their network of friends. Gaming is usually a go-to activity when they are bored, or have nothing else planned. Several participants reported gaming as being their default activity during idle times such as after coming home from work/school, on weekends, or during breaks, as illustrated by Micah’s quote:

Although participants used games to fill idle time, they also specified that gaming requires less effort or is “easier” than some other activities. Gamers felt that it was easier to game than to participate in other hobbies, study, do chores, or even to think of another activity do. Since most participants played after they returned home from school or work, they reported feeling too tired to engage in anything else other than gaming. They felt that other activities are too much “trouble” (i.e. takes time to set-up or involves special equipment), involve leaving the house, or are perceived to be “difficult”. They revealed that in contrast, they can play video games within the comfort of their home while still feeling like they are “doing” something because of the endless possibilities that video games offer.

3.1.2. Gaming community as a sub-culture

Sub-cultural groups in society are those who have beliefs or interests that differ from the dominant culture. These sub-cultural groups are often viewed as subordinate; people belonging in these groups are denounced, side-lined, canonized or treated as harmless fools (Hebdige, 2002). Participants spoke about the gaming community as a sub-culture that is sometimes misunderstood by the dominant culture. All participants had a network of friends who shared similar interests in video games and shared experiences either by playing together or attending gaming events/conventions together. They also reported using games as a way of staying in touch with friends who live far away—even in different countries. Mercedes described travelling with her boyfriend from Canada to visit friends whom they met while playing online games:

Participants reported not only being able to bond with existing friends through games but also make new friends. Melanie revealed that she invited someone she met through online gaming to her wedding where they finally met in person.

Although the gaming community is viewed as accepting and positive by participants, some adult gamers described feeling misunderstood by those who do not play. Roy explained that gaming affects his current relationship because his partner does not feel it is an age-appropriate activity for adults.

Some participants perceived that those who do not play video games believe adults should not be gaming, and that this lack of acceptance of gaming as a mainstream hobby leads to their feelings of being segregated from popular culture. Bernard explained in a follow-up email after his interview that gamers can become increasingly closed off from those who do not share an interest in gaming.

Participants felt that it is difficult for outsiders to understand gaming as a hobby and they perceive the activity as “wasting time”. Because of this, Melanie reported that she experiences “guilt that I want to play”. However, many participants in this study sought out opportunities in which they were amongst others who enjoy gaming, which perpetuates their gaming habits and the gaming community.

3.1.3. Gaming as a purposeful activity

According to participants, the purpose of video games in their lives included offering opportunities to relax, exert control, be challenged and achieve goals. They reported that games help them de-stress and unwind after work. Mark reported games helped him “relax” after returning to the comfort of his home. Participants also reported that they played because games were enjoyable as well as provided a sense of control. They controlled in-game characters and as Kurt described it, make “multiple choices” where “you feel like your actions really come into play”. Some participants asserted that gaming was an activity that can be done alone or in the company of friends (online or in person). It was also conveyed that games offered adventure through role-playing and stimulated creativity. One participant confided that games inspired her art work: [Video games] make me want to draw more or, like, have ideas to make other stuff because I craft a lot too.

The most dominant role of games reported by participants was the challenge and sense of achievement they provided. Games were not viewed as a passive activity, but rather, one where participants were motivated by challenge and game related self-improvement as Bernard described:

Participants discussed feeling a sense of achievement when they won or accomplished something within the game, especially in games with skill ratings and rankings for each individual player. The gamers described a “sense of exhilaration” and feeling “validated” through gameplay.

3.2. Theme 2: Push and pull influences on the amount of gaming

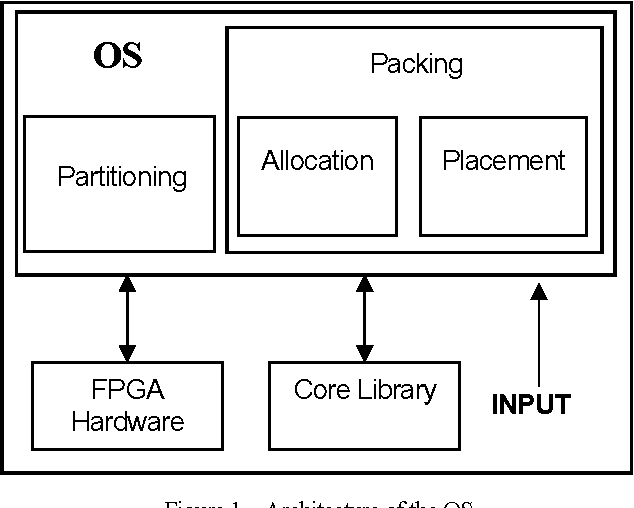

Push and pull influences on the amount of gaming emerged as a pervasive theme. Specifically, various forces influence choices on the amount of gaming. Personal, interpersonal, and environmental influences pull gamers into games or push them away from games (see Fig. 1). These forces are sometimes within the individual (e.g. they play because they enjoy it) and sometimes external to the individual (e.g. they play because of influence from friends or because there is nothing else available for them to do in their community). The dotted-line around the “Amount of Gaming” in Fig. 1 connotes the ability for the amount of gaming to expand or contract based on the pushing and pulling of the influences. The three influences–personal, interpersonal and environmental—also converge and do not exist in isolation; each of them push/pull on the amount of gaming simultaneously. For example, a person may want to stop gaming because he is tired, however his friends encourage him to play one more. These influences will be further described in the sections below.

3.2.1. Personal push-pull influences

Personal influences reported by participants included their sense of responsibility for other tasks and roles, planning/scheduling, and meeting self-care needs. These needs and tasks competed with the perceived meaning and purpose that participants derived from video games. The most salient personal influence that pushed participants away from gaming was the sense of responsibility—usually associated with a productive activity such as work, school or volunteering. When participants believed that they are engaging in other meaningful activities, they would forego games. Evan described his sense of responsibility in activities other than gaming:

This sense of responsibility comes from being accountable to oneself (e.g. make money to pay the bills/buy things) or to others (e.g. being a caregiver for a family member).

Two participants described how spirituality and prayer helped them gain a sense of “clarity” and “strength” to put other tasks ahead of gaming. Micah discussed attending church during holy week and reflecting on his life:

Micah’s comments demonstrate his recognition that building a life outside of gaming is more meaningful to him than staying in his apartment playing games.

Gamers’ sense of responsibility must outweigh the meaningfulness of gaming to push them away from gaming. There may be occasions where gaming takes priority. Emily described using volunteering to control how much she games by booking her volunteer hours on weekend mornings. However, she disclosed that because she enjoys the competitive side of video games, she has sometimes prioritized gaming over volunteering. She described one occasion when she signed up for a video game tournament and cancelled her volunteer activity one weekend in preparation for the tournament so that she did not let down her teammates. Marcus also described skipping a class he did not feel was meaningful to attend because all of the class material had already been posted online and instead opting to play video games at home. Participants’ stories revealed that gaming can outweigh participants’ sense of responsibility if they do not feel the other activity is worthwhile.

As noted earlier, participants often played video games during idle, unstructured times. Intentionally planning time by filling their schedules with other activities was expressed by some participants as a way to push themselves away from games. Although scheduling other activities in their day was not guaranteed to stop gaming, participants often reported that it helped them to set boundaries for gaming. Several participants reported setting an alarm to remind them to stop gaming and move onto the next activity such has going out with friends or studying for school. Cynthia suggested that it would be helpful for game developers to embed customizable scheduling functions within the games to help her manage her daily activities where the game would “cut off to make you stop so you could go do whatever you need to do next”.

Other participants found enjoyment in alternative activities and participated in them rather than gaming. These participants reported going on excursions around their city or travelling to other destinations as stimulating and like an adventure. Although Mark was pulled to play video games to de-stress, he also reported that going to the gym energized him and gave him motivation in life and therefore pushed him away from gaming. Melanie reflected on the choice to engage in other activities, stating that accessibility was important:

Participants felt they needed to choose other activities that also offered the sense of challenge and meaning that many video games offer. For example, two participants described starting hobbies that were difficult but provided them with a sense of challenge and pride (e.g. making sourdough bread and dancing).

While some basic self-care tasks such as using the toilet were completed as needed, others such as sleeping, eating, and bathing were all negatively affected by gaming. Participants went to sleep later than intended, skipped meals or ate smaller meals, skipped bathing, and/or neglected physical bodily pain (such as neck and shoulder pain) to continue gaming. At other times, participants set alarms to remind themselves to stop gaming and to go to sleep. Some participants reported foregoing games to catch up on sleep another day (usually on weekends). Even though sleep appeared to be sacrificed for gaming, ironically, it was common for participants to also use gaming to fall asleep or fall back to sleep if they woke during the night.

Another personal “pull” influence on the amount of engagement in gaming was the extent in which participants found games to be helpful as a coping method for negative feelings or negative life events (such as death of a family member or breakup with a partner). It offered an immersive way to “escape reality” and frustrating situations, as stated by Arnold:

Participants acknowledged that using games as a coping method only offered temporary relief from their negative emotions and did not address the problems they were facing. Bernard described using games to feel good and avoid frustration as he struggled to understand some complex concepts he was learning in school. However, after gaming, he realized he had “wasted time” and could have spent that time studying and trying to understand those concepts. Two participants reported playing even though they did not enjoy it anymore, but, continued to use games “like a drug” that “made them feel worse” afterward. They realized that games were not a solution to their problems, but rather, mimicked addiction-like symptoms.

3.2.2. Interpersonal push-pull influences

Interpersonal influences that include co-habitants (family members and partners), friends, social apps/websites, co-workers, teammates, and therapy were highlighted by participants as influences on the amount of video gaming. All participants reported starting gaming at an early age (in primary school) when a parent or other family member supported their engagement with video games either by playing with them, purchasing games for them, or rewarding them with games for doing well in school. Participants who talked about gaming cessation also spoke about parents or family members who helped them engage in other activities—either another hobby (e.g. skateboarding) or productive activity (e.g. finding a part-time job). Participants who lived with their parents and other adult participants reflected on parents’ influence on gaming. Those who lacked supervision or engagement from their parents (e.g. time to talk to their parents about their lives) reported being stuck in an intense gaming period for a longer. It was particularly problematic for Ivan; he played games as the only other activity outside of attending school since early childhood and reported his parents would bring him food to eat at his computer so that he could continue gaming. He lamented that he did not receive encouragement from them to participate in any other activities.

The influence from others who lived in the same household, such as siblings and romantic partners, was different from parents. Participants reported playing with them as a form of bonding but were also pushed away from gaming because of wanting to better themselves in other ways or feeling guilt/shame for playing. Emily described gaming with her boyfriend, and at the same time, trying to stay accountable to each other:

As evidenced above, co-habitants can act in different ways to pull gamers to play more games and/or push them away from gaming.

Participants were not socially isolated and were often pulled into playing games when friends asked them to play online. Gaming was frequently used to bond with friends or co-workers. It was also described as a way to stay in touch with out-of-town friends as they played together through voice-chat. Brian described integrating video games into his volunteer activities where he ran a language exchange program:

Participants reported that other influences pulling them towards games are when friends back out of in-person plans, they meet new friends online, and when they use games to reveal friends’ personalities in a different way while playing online together. Adam described how his friends’ personalities can be amplified through a game:

Not all participants were part of the gaming community as described in the section on the sub-culture of gamers. Some participants who played in isolated situations reported that they may have missed out on exercising their real-life social skills. Their drive to interact with real-life people pushed them away from gaming. Some were pushed away from gaming because of obligations to real-life teams or organizations. Other forces that typically pushed participants away from gaming in these cases were negative—or “toxic”—online players.

One participant reported receiving therapy for personal issues but used it as a way of understanding himself to push him away from gaming. This participant reported that talking with someone helped him understand that he was using gaming as a “easy” and “reliable” way to get the “stimulation” and “attention” that he needed but was not offered by his family. Even though his therapy was not targeted at video gaming, he consciously tried to decrease his time spent gaming and to engage in other activities.

Finally, websites and digital applications were also found to influence the amount of gaming, depending on its function. Apps and websites that acted as pulling influences included fanfiction websites, gaming forums, team-chat apps (e.g. Skype, Discord, Teamspeak, Ventrillo, etc.), Steam (a game-purchasing app with a social component), gaming bookie websites for gambling, and video streaming websites (e.g. Twitch). Participants reported that they would watch gaming-related videos on YouTube.com that would make them want to play longer.

In contrast, interpersonal apps and websites that pushed gamers away from gaming involved online support groups, chat/dating apps, and exercise/activity apps with a social component (Habitica and Couch to 5 K were mentioned). Ivan reported that reading personal stories of gamers who were trying to quit playing video games on the StopGaming thread on Reddit.com helped him stop playing games for at least 82 days and focus on other activities.

3.2.3. Environmental push-pull influences

Environmental forces that influenced the amount of gaming revealed by this study included game features, physical setting, and environmental supports and constraints to access to activities. First, participants noted that games are designed to be attractive, fun, and “addictive”. Participants described games as interesting, visually appealing, and allowing them to experience infinite possibilities through gaming. Sometimes the game design was so enticing that participants reported playing even though they “hate” it. Lianne talked about enjoying the game design even though she felt nervous playing it and did not like the genre:

Different genres of games and game features are designed to pull players in and keep their attention in different ways (e.g. storylines for exploration or shooter games for excitement). Participants described mobile and non-mobile games being modeled after gambling principles. Random loot or better characters can be awarded for gameplay. Furthermore, Ivan described underage gambling occurring through video games and on digital platforms/websites related to video games. A participant believed that the game developers not only try to make games “addictive”, but that some also try to entice gamers to play several games at once by offering in-game rewards for one game by playing another game by the same company. She also reported that players are punished if they leave in the middle of a game (by losing ranking points or being temporarily blocked from playing the game). However, not all games are captivating. Participants reported stopping to play another game or engaging in another activity if the games do not create a just-right-challenge. Participants often stopped playing out of frustration or anger towards the game. They also stopped playing if they became bored with the game.

Second, the physical setting in which the individual is situated can influence the amount of gameplay. Participants reported retreating into their rooms to play when they lived in households where there are frequent arguments or conflicts. Micah described his environment in the following passage:

Evan, who lived in a small town, reported that there was not much to do in his town, so he spent his time gaming. Both Lianne and Roy talked about living in environments that were dangerous. Roy pointed out that he could have potentially become involved in gang activity if he did not stay home to play video games. Others reported pulling influences towards video games were due to the lack of physical space at home to do other activities and when the weather outside was bad, so they preferred to stay in.

In contrast, if participants enjoyed their physical environments, they tended to play less and engage more with other activities. This frequently occurred when participants were away from home. When away from home, they typically reported that there were other things to do or they preferred to be with their friends. Sometimes being away also meant that they did not have access to their computer where the games were installed and would only occasionally play mobile games. Alternatively, if participants were doing something else that involved their gaming computer (e.g. for homework or entertainment), starting a game was an “easy transition” because they were at their computer already.

Lack of access to computers (e.g. broken computer or lack of finances to fix a computer/buy an expensive game) also prevented gaming. One participant reported intentionally blocking her access to games by changing all the passwords during exam time. In such situations, participants reported they would need find something else to do. Similarly, barriers to participation in other activities included a lack of: finances to do the things they were interested in, access to the physical space required, and knowledge in resources that were available to them in their communities. Some participants simply reported that they did not know what else there was to do. In summary, personal, interpersonal, and environmental forces converge to push and/or pull in ways that regulate the amount of gaming.

4. Discussion

This study uniquely sampled only PGs to reveal findings that were directly related to function and their lived experiences. The social ecological perspective offered a lens that directed this study to focus more on external influences rather than individual (psychological, biological, neurological, etc.) explanations for problem video gaming that previous research had focused on. A unique aspect uncovered was that spirituality contributed to the amount of video gaming a PG engaged in. Spiritual aspects of a person have been cited as a moderating factor for internet addiction (Lopez-Fernandez, 2015), but not for problem gaming, specifically. Understanding that gaming facilitates meaningful occupation and function—even for PGs—implies that they are more like non-PGs even though they were previously thought of as dysfunctional. The unique interactions found in this study between the push/pull characteristics in the lives of a PG could help researchers, policy makers, and health care workers in this field. The prominent themes uncovered by this study contribute to the study of problem video gaming and may also be useful in the study of other behavioral addictions.

This study found that PGs experience both positive and negative impacts on their lives from gaming. Although some PGs’ interpersonal relationships might be strained by gaming, other PGs also revealed how relationships can also be strengthened. Furthermore, interpersonal relationships can be a support to them; it can enable their participation in other life activities. Gamers in this study described being motivated to play for: socialization/friendships, the opportunity to exert control in their lives, enjoyment, inspiring creativity, discovering a sense of community, challenge, and relaxation. They were also motivated to game to cope with other life stressors and to appreciate the game design. These motivations are similar to the motivations found by previous research (Dauriat et al., 2011; Yee, 2006) with non-problem and PGs. But, this study also added nuance to this discussion; PGs felt particularly “addicted” and suffered functionally when motivated to play while using gaming as a coping mechanism (e.g. unable to deal with other life stressors such as school work or family issues). Previous research found that gamers felt worse when they used gaming in this way and felt they had wasted precious time (Snodgrass et al., 2014). Other researchers have also stated that gaming “disorder” is not a disorder itself, but a consequence of using games as a way of coping or meeting other life needs (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Starcevic, 2017). In this study, the culprit was not video gaming itself but a lack of effective and healthy coping strategies. Seeing that this is a trend in research with PGs, therapists can be a valuable support for promoting balanced life activities teaching alternative evidence-based coping strategies for PGs’ personal issues. These findings question the justification of gaming disorder as a diagnosis versus being the product of other issues.

Unique to this study is the finding that some PGs were engaged in gaming to fill idle time and if they were too tired/lazy/unable to do anything else. As such, it is particularly important for PGs to have activities in life that offer choice and control to prevent occupational deprivation (or boredom) (Townsend & Polatajko, 2013, pp. 71–80). Boredom is a lack of engagement in meaningful activity and consequently a lack of function. Therefore, boredom may be a contributing influence on PGs’ continued engagement in problem gaming, similar to how it could contribute to high relapse rates among substance abusers. A study on gaming abstinence among young adults conducted online found that boredom and a need for mental stimulation was experienced by gamers who did not play for 84 h (King, Kaptsis, Delfabbro, & Gradisar, 2016). Furthermore, studies have found that restricting gameplay alone, without introducing other forms of meaningful activity will have minimal positive effects on PGs. Due to concerns with problem gaming, the governments of Korea, Hong Kong, and China took steps to restrict gaming activity (Birtles, 2017; Williamson, 2011). While the effectiveness in regulating video game play has been scarcely studied, Lee, Kim, and Hong (2017) found that the shutdown law in Korea had minimal positive effects on regulating gaming but yielded negative outcomes on gamers. It can be inferred, therefore, that interventions aimed at reducing video game playing should also introduce other forms of meaningful activity, simultaneously. The new activities should be introduced in a planned and accessible manner in light of this study’s findings that accessibility is a reason PGs engage in gaming. Activities selected to fill blocks of idle time should meet the needs of the individual—that is, whether they want challenge, achievement, adventure, and so on.

Although the benefits of gaming and the motivation underlying it are evident in this study, it was found that gaming sometimes tended to override some other functional activities, such as the need to fulfill self-care needs. Sleep and proper nutrition are important issues to consider with PGs since sleep can affect physical and mental health (Moore, Adler, Williams, & Jackson, 2002). Participants reported skipping meals or taking quick meals at their computers which impacts psychosocial well-being (Eisenberg, Olson, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Bearinger, 2004). The finding that gamers typically ignore these self-care needs is concerning and requires further attention. If excessive gaming is an issue, addressing basic self-care tasks first is important for the physical and mental well-being of the individual.

4.1. Application of the push-pull influences

The push-pull influences on the amount of gaming that a PG engaged in, found in this study can be practically applied to interventions with PGs. Managing the amount of gaming a PG engages in involves leveraging personal, interpersonal, and environmental supports to participate in other meaningful activities outside of gaming. It could also mean that sometimes access to games should be removed or restricted. As participants indicated, blocking access could be self-imposed or negotiated with someone else living with the individual. If access to gaming is withheld, it is important to provide meaningful productive activities that provide a sense of responsibility, such as paid or volunteer work. These activities could be used to fill the large blocks of time that were previously devoted to gaming. This is especially important to implement considering the amount of previous research citing productivity issues (Cole & Griffiths, 2007; Hastings et al., 2009; Hellström et al., 2012).

Participants in this study were unable to identify policy or regulatory supports that would help them engage in other activities. This suggests a current lack of support from a policy standpoint from gamers’ perspectives. The suggestion from Cynthia to equip games with built-in schedulers could be an avenue of regulatory exploration. Parental guidance was the only type of regulatory support reported by participants. Some participants in this study reported that their parents encouraged them to participate in other activities; others who did not have this encouragement reported that they wished their parents helped regulate their gaming more. Schneider, King, and Delfabbro (2017) have also suggested addressing family issues when intervening with problem gaming. Regulations for video game play might serve to help young gamers who do not have parental guidance or supervision. Enacting legislation to apply limits on video game play might be more effective alongside promoting other activities and opportunities for gamers to discover other leisure activities that they are interested in and learning to control the amount they play in the future.

In the same vein, as participants reported that gaming is a part of their lifestyle and it is also their “default” activity, the importance of introducing new experiences and activities to youth to broaden their awareness of their range of choices is emphasized here. This is not to say that gaming is an undesirable activity, but because it is mostly sedentary, it should be complemented with activities that promote physical activity. Physical exercise promotes not only physical health, but, also mental well-being (Fox, 1999). Social assistance programs and/or financial incentives should be implemented to support caregivers in enrolling their youth in physical activities. An example of such support is the children’s fitness tax credit that provides a claim up to $500 per child per year for program involving physical activity by the government of Canada (Government of Canada, 2017). Such support and the promotion of engaging programming for youth is crucial in promoting overall health and well-being, particularly with low income households.

Finally, another concern found by this study is regarding the lack of regulations and/or policy controlling the use of gambling features within video games. Many games have incorporated elements of gambling into their designs such as attractive sounds and colours, bonuses, and the illusion of skill (Griffiths, 1999). Furthermore, Griffiths and King (2015) argue that mini-games within video games appear to meet the criteria for gambling. The government of China is intervening in this issue by mandating gaming companies to announce the random drop rates of “loot” within their games (Tassi, 2017). This study, however, did not support an explicit link between engaging in problem gaming and problem gambling. As a precaution to combat problem video gaming, greater onus should be placed on video game publishers to support their users’ health. Just as there are typically no clocks readily visible in casinos, most games do not show the time even though the game fills the screen and immerses the player. A simple solution to this would be to mandate game publishers to integrate a built-in clock into their games. This feature might help gamers who reported using planning/scheduling as a way to maintain their schedules and lead a well-balanced lifestyle.

4.2. Limitations & future directions

This study sampled a worldwide population and therefore gained culturally and socially diverse views of the lives of PGs. A broader participant pool that did not involve only English speakers may have revealed different results. This study focused on gaining an understanding of the perspectives of problem gamers to contribute to the discussion of gaming disorder from first hand experiences. Video game genres are constantly evolving. There is also an increasing percentage of female gamers (McLean & Griffiths, 2013; Pew Research Centre, 2017). Consequently, this study did not delve into the nuances of game genres, gamer genders’, or cultural/geographic influences on participant responses. Instead, this study aimed to grasp an overall understanding of gamer perspectives. The purpose was to gain diversity in PG perspectives. Adding a diverse range of perspectives strengthens this qualitative study (van den Hoonaard, 2019, pp. 1–54). Further research could examine the effect of game genres, gender, and cultural aspects on gamer perspectives.

Regarding recruitment and screening of participants, none of the participants were referred by clinicians even though emails were sent through the listserv and treatment websites; results could have differed with participants who were currently in treatment for problem gaming and who may have had more severe issues with problem gaming. Furthermore, due to the lack of theoretical research and lack of a definition for problem gaming, it may be the case that participants scoring five or more out of nine questions on the PVP scale was too low of a threshold. Nonetheless, this study based decisions on the cut-off score on previous studies to establish consistency in scale use. The determination of problem video gaming requires further theoretical investigation through qualitative and quantitative research with clinical populations of PGs.

The process of understanding PGs will be iterative and best done with a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. As this study found, problem gaming is not solely a function of individual gamers but influenced by interpersonal and environmental forces as well. Quantitative research can be completed as a follow-up to test the generalizability of the findings from this study in terms of themes, motivations, supports, and constraints found. Since participants in this study encountered difficulties tracking their weekly time use, caution should be taken with survey studies that ask for “time spent gaming”. This study found multiple gaming-related activities that PGs engaged in aside from just gaming time. Therefore, actual time occupied by video games are much higher. Questions asked should include both physical time spent gaming and time spent on gaming related activities. As this study has gained valuable insights using qualitative research methods, future studies could engage different qualitative approaches to understanding the phenomenon of problem video gaming. With the growing video game industry and increasing accessibility to video games, future studies can investigate how new generations are influenced by video games, what their perceptions are on problem video gaming, and further examine the link between problem gaming and gambling.

5. Conclusion

This research uncovered the importance of interpersonal and contextual issues that may have been previously overlooked in gaming disorder literature. Interpersonal, spiritual, and environmental (both online and offline) aspects of PGs’ lives contribute to how much they play video games. Problem gaming literature should be distinguished from Internet addiction and other behavioral disorders such as problematic gambling since certain aspects of motivation such as exerting control and the achievement/challenge aspect of gaming are unique to this population. This study also contributed to the discussion of examining daily activity as part of defining functional impairment in behavioral addictions. This study found that PGs experience both functional enablement and functional disruption due to video gaming. Video games were found to be meaningful and purposeful to PGs, similar to non-problem gamers. It also supported activities at work and other leisure activities. However, when gaming was used as a form of coping with other life stressors, it disrupted lives in negative ways.

This study identified push-pull forces that influence the amount of gaming PGs engaged in, and these can be used to moderate gaming use amongst PGs. Traditional settings for social activity have changed rapidly with technology (Kennedy & Lynch, 2016) and evidence for a sub-culture of gamers has emerged (Grooten & Kowert, 2015). The gaming culture is relatively new and has advanced quickly while society’s perceptions of gaming as being for children have remained the same. This study challenges the notion that video games are only for children. Adult participants revealed that video games were a meaningful activity in their lives. With this in mind, conventional leisure activities for children as well as adults should be closely examined. PGs understand what activities offer them a sense of meaning and personal growth. However, in cases where gaming is used problematically to a point of harm or impairment, intervention may be needed to address underlying life issues and control video game use. Similarly, if PGs wish to decrease the amount of gaming and participate more in other activities, environmental and interpersonal issues need to be considered in additional to personal issues. Constraints (pull forces) to these activities need to be removed and adequate supports (push forces) need to be obtained to enable their desired participation in life activities. Interventions that address problem gaming should consider placing more of an emphasis on interpersonal and environmental issues in conjunction with individual issues as a more holistic approach to care.

[“source=sciencedirect”]